Curriculum Directory

The curricula featured here invite engagement, both by the content students are exposed to and the way in which the instruction draws students in. These curricula spur students to explore topics and inspire them with a desire to learn more. In short, these knowledge-rich programs restore wonder and curiosity to ELA instruction.

Understanding knowledge-building curriculum

To help students make sense of what they’re reading, knowledge-building ELA curricula are intentionally designed to build a deep and wide knowledge base in the various fields of science, history, literature, and the arts, starting in kindergarten.

They are also designed around the essentials of sound reading instruction. Students must be powerful readers to become self-reliant knowledge-seekers throughout their lives!

Building knowledge of the world—even building knowledge of a topic—is a cumulative endeavor, with ever more sophisticated understanding growing over time as the result of multiple exposures to the content. Building knowledge is entirely different from activating knowledge; it starts where little is—and it must begin in the earliest grades.

US elementary schools spend very little time on science and social studies (between 1–2 hours per week each, according to multiple studies), so time spent in English language arts/literacy (between 10–15 hours per week) should coherently build knowledge while reading, writing, speaking, and listening are being mastered. Here, we explore K–8 programs that meet these objectives.

Characteristics of effective ELA instruction

Research tells us that the following ingredients are crucial in students’ ability and intrinsic desire to read well:

- Coherently building knowledge of words and the world.

- Teaching students to read through systematic foundational skills instruction until word recognition is automatic and students are fully fluent.

- Affording every student access to focused, close communal reading of content-rich complex texts.

The curricula spotlighted here meet all three crucial elements and empower students to become capable, effective, and motivated readers and writers.

Importantly, these curricula look and feel very different from traditional basal readers and popular “balanced literacy” programs, which encourage many practices that have largely been discredited by research. In addition to taking a haphazard approach to building content knowledge, such programs generally focus lessons on single skills (like “find the main idea” or “draw inferences”) or isolated standards. They typically embrace a leveled reader approach that denies many students access to rigorous texts. Finally, the sheer bulk and bloat (“kitchen sink” approach) of every basal program examined dilutes any individual strengths it may contain.

Read more about the issues with commonly-used ELA curricula.

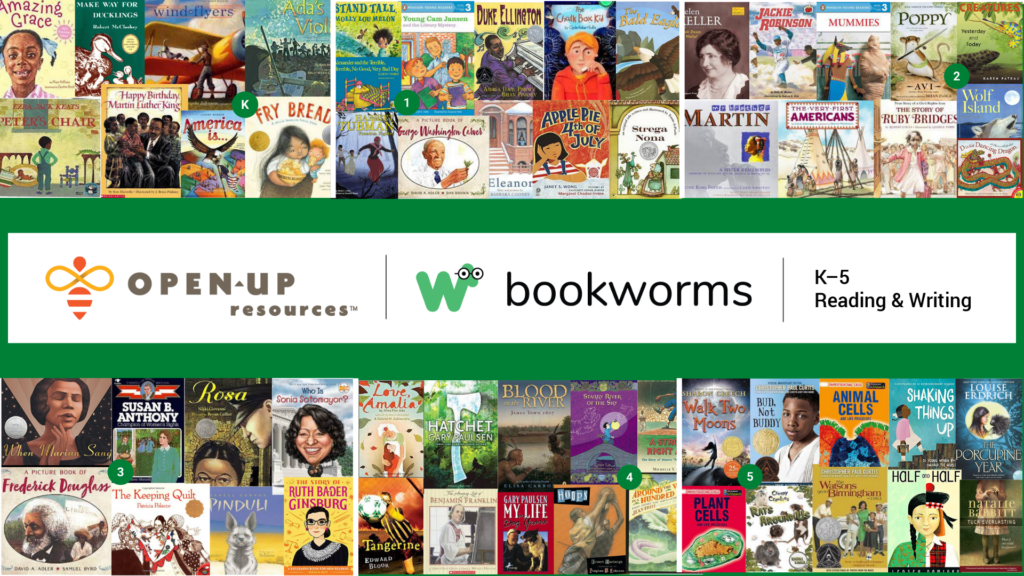

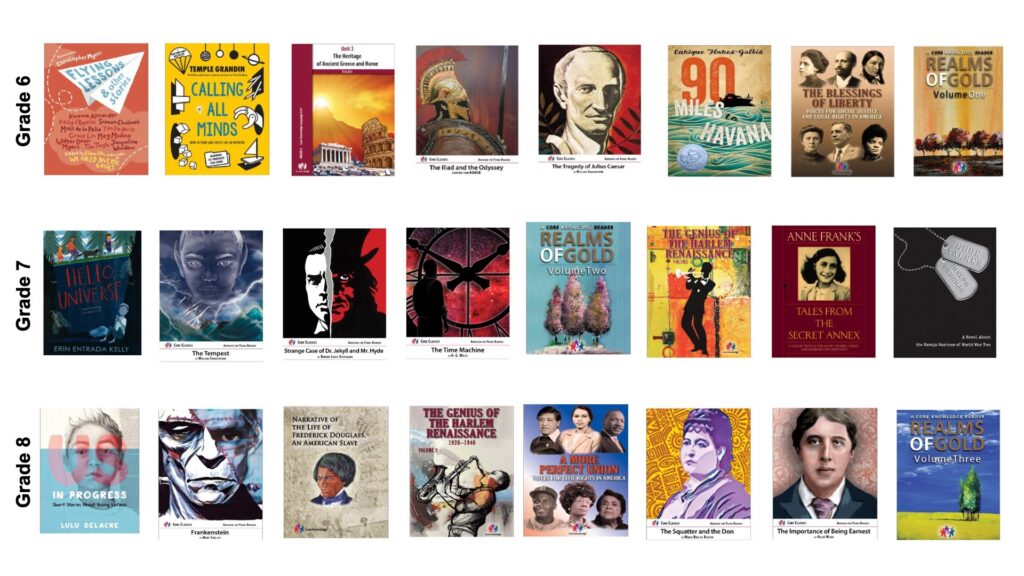

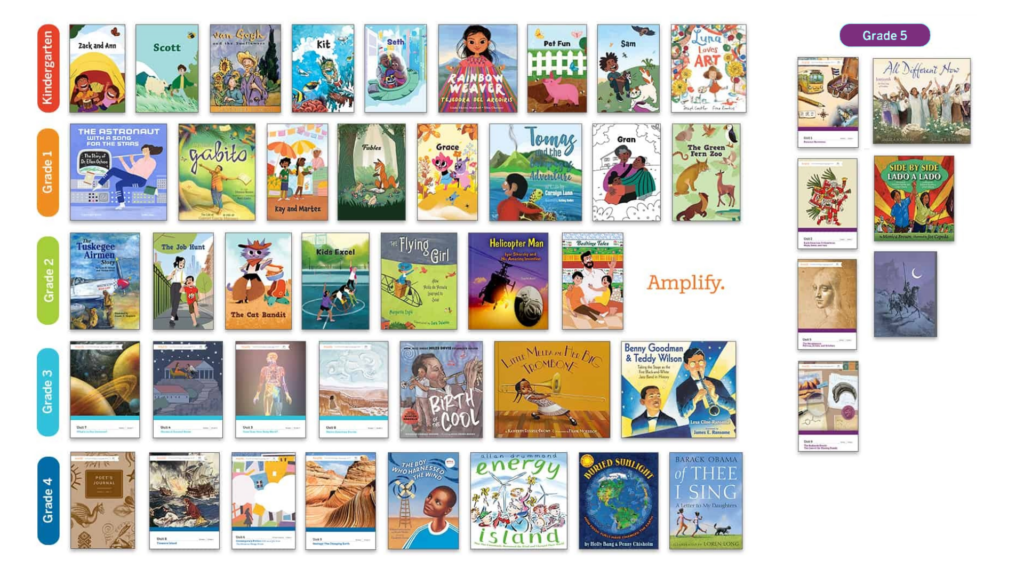

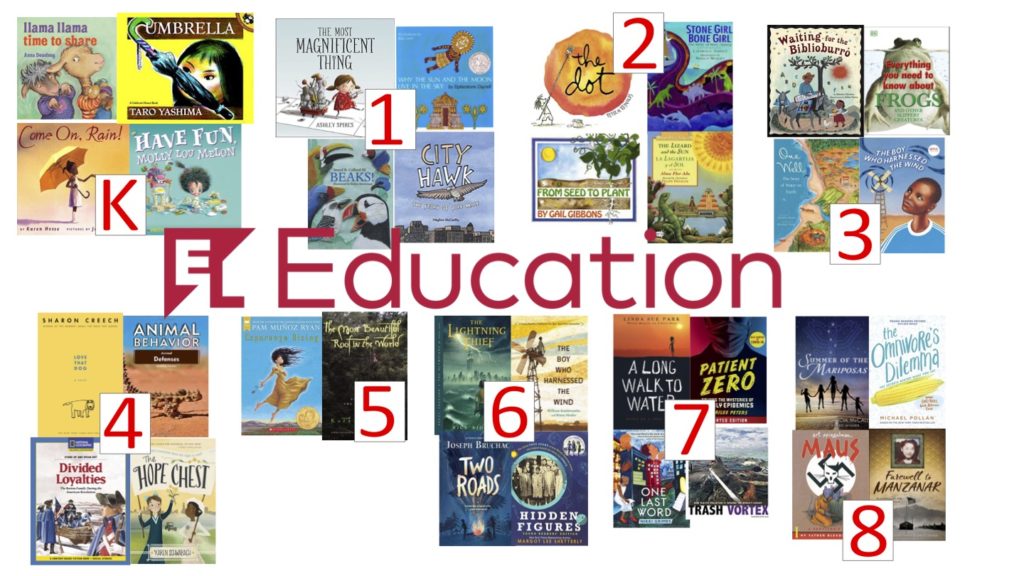

ELA programs that excel in building knowledge

In our estimation, 10 English language arts curricula currently meet the criteria for knowledge-building detailed here.

While these curricula share common virtues and are all solidly grounded in what matters most for literacy, each has a unique and compelling identity. They present students with substantive, rich content and lack “fluff.” They support access for all students. They motivate and engage students through their content and design. They help all students achieve at high levels. And teachers get ever better at their craft by using them.

Learn what characterizes each curriculum – and gives all of these materials an advantage over programs that are organized around strategies and skills.

How these ELA curricula build knowledge for all learners

Knowledge-building curricula go deep on content:

A volume of texts and other resources consistently deepen students’ knowledge incrementally on a given topic, spending anywhere from three to eight weeks on that topic. In addition, questions, tasks, and activities utilize content from and related to the texts.

This is a real contrast with most other English language arts curricula, which prioritize a focus on isolated skills or standards, and only touch on texts and topics as their vehicle for doing so, while the content takes a back seat.

These curricula are designed around worthy texts that invite students to learn about, and become interested in, the natural and human world in deep, connected, and meaningful ways.

Research tells us this concentration on content—on building knowledge about the world—profoundly influences students’ intrinsic motivation to read and strengthen their self-efficacy.

These curricula provide equitable access to content:

Knowledge-rich programs invite all students to learn together about the world at high levels. They recognize students’ innate drive to explore, learn, and grow. Unlike traditional ELA programs that label some readers as “weak” and deny them access to challenging texts and content, knowledge-building curricula systematically provide all students with access to vital and rich content. Teachers report heightened levels of motivation and desire from all students, especially weaker readers who are now working right along with the whole class. That’s no surprise. Young people are astute at knowing whether the work they are being asked to do respects their brains; they tend to respond by putting their best effort forward in class.

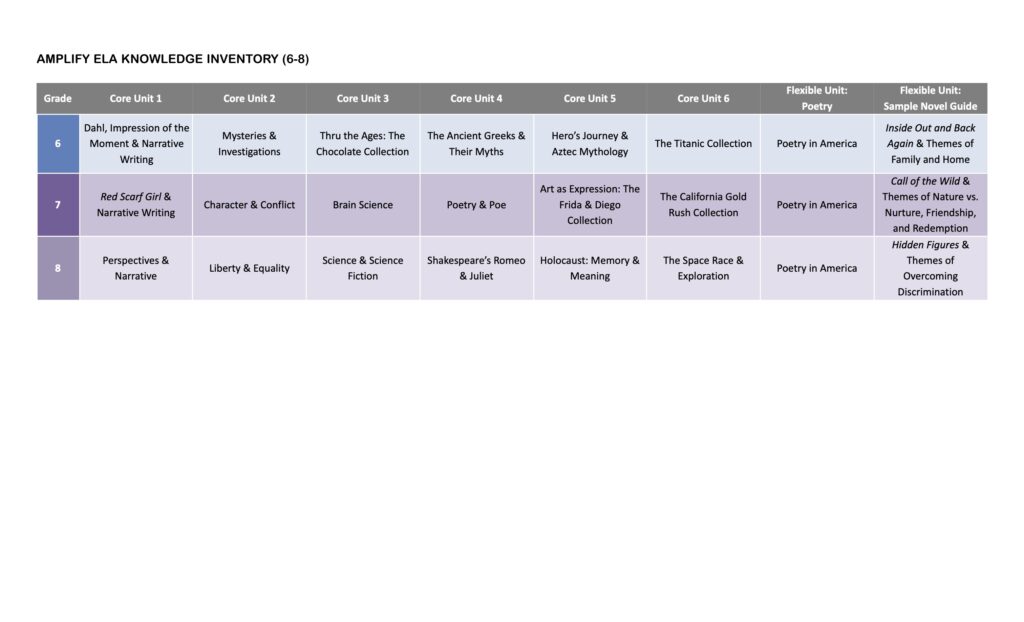

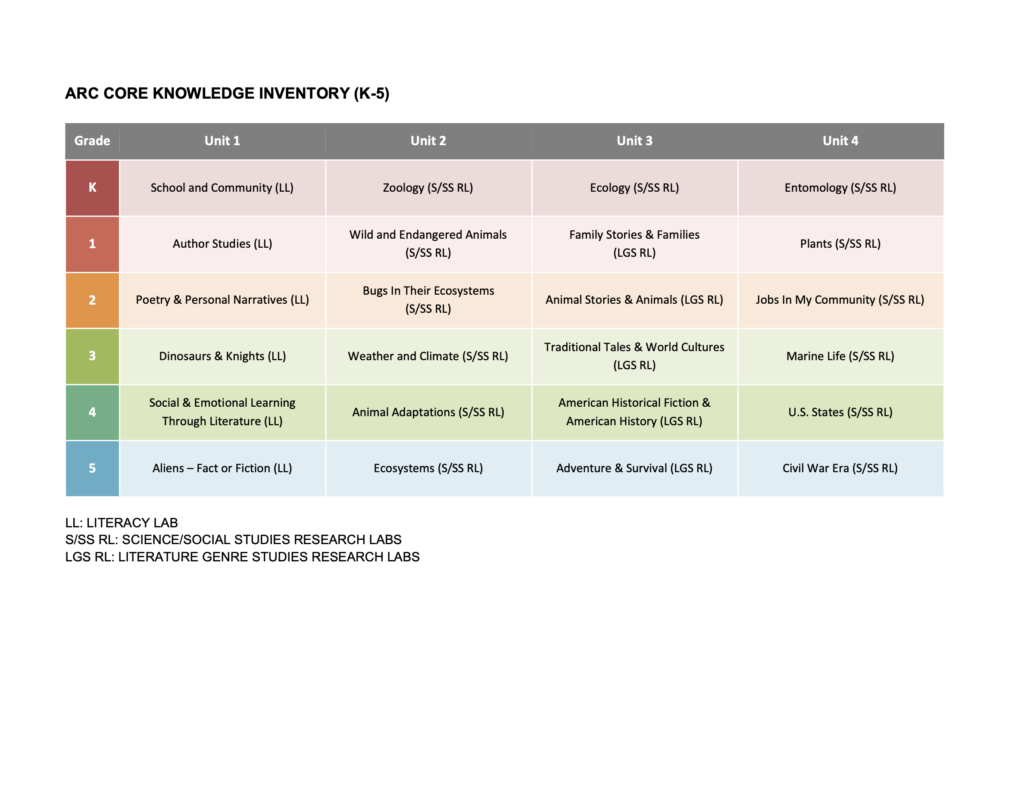

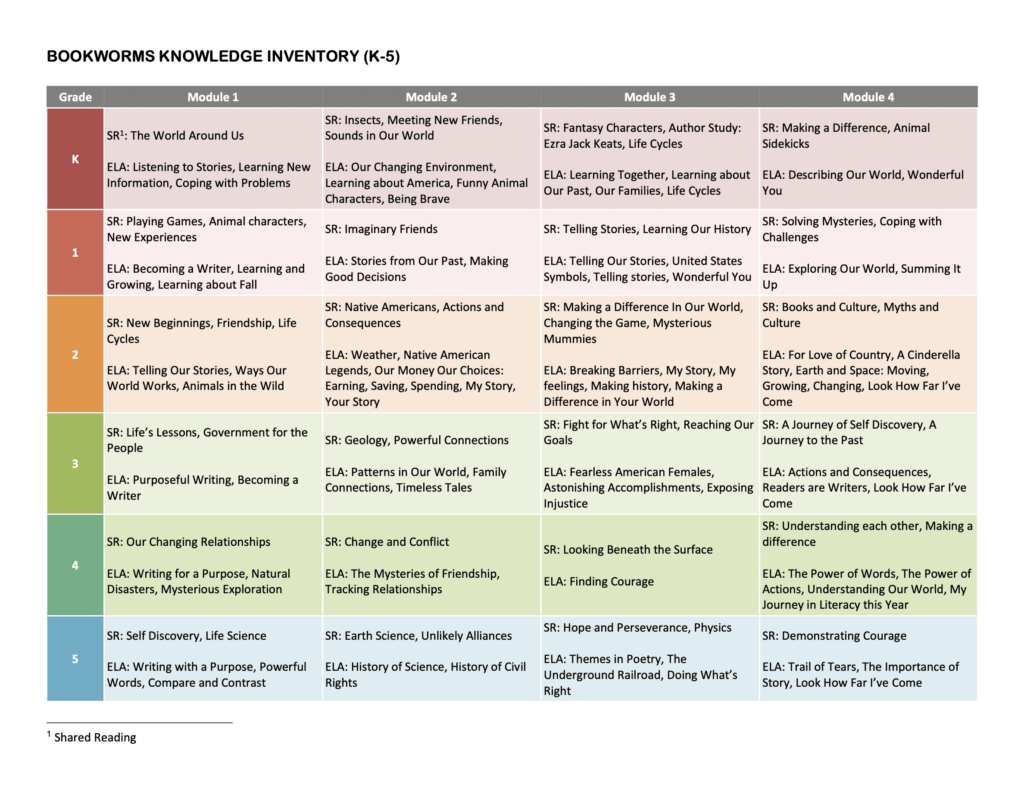

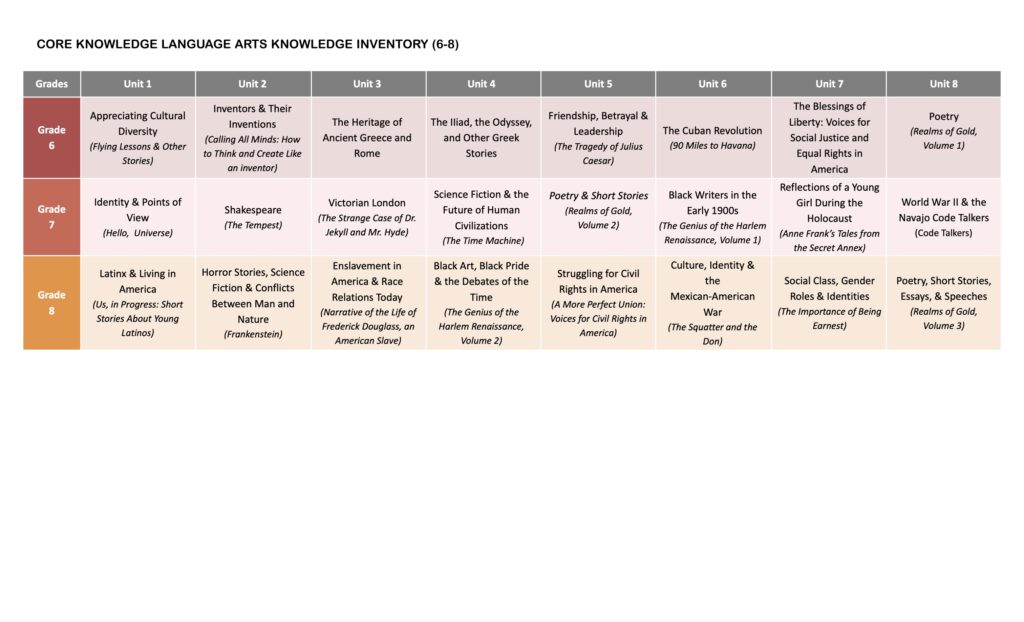

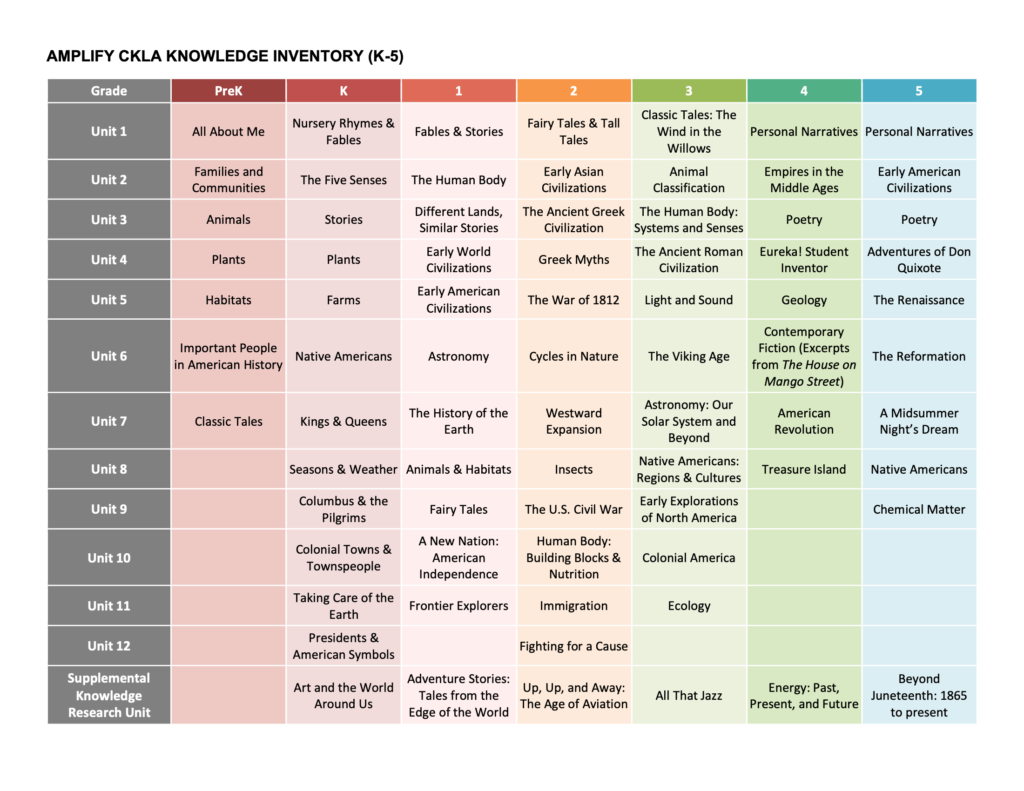

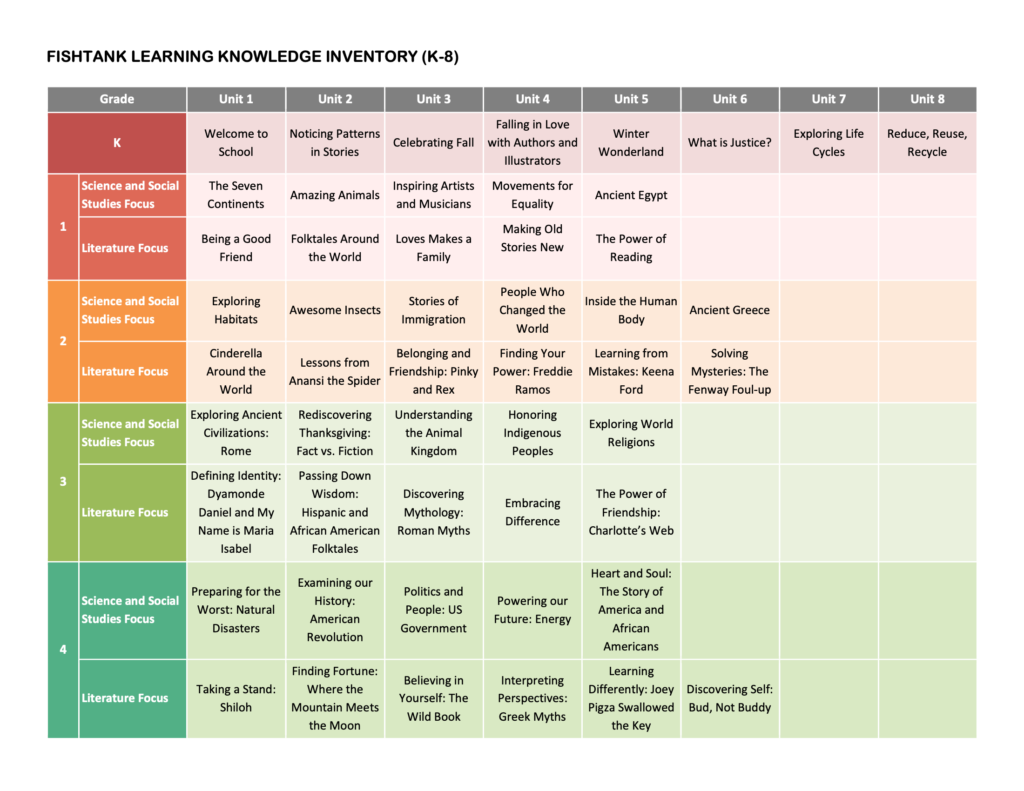

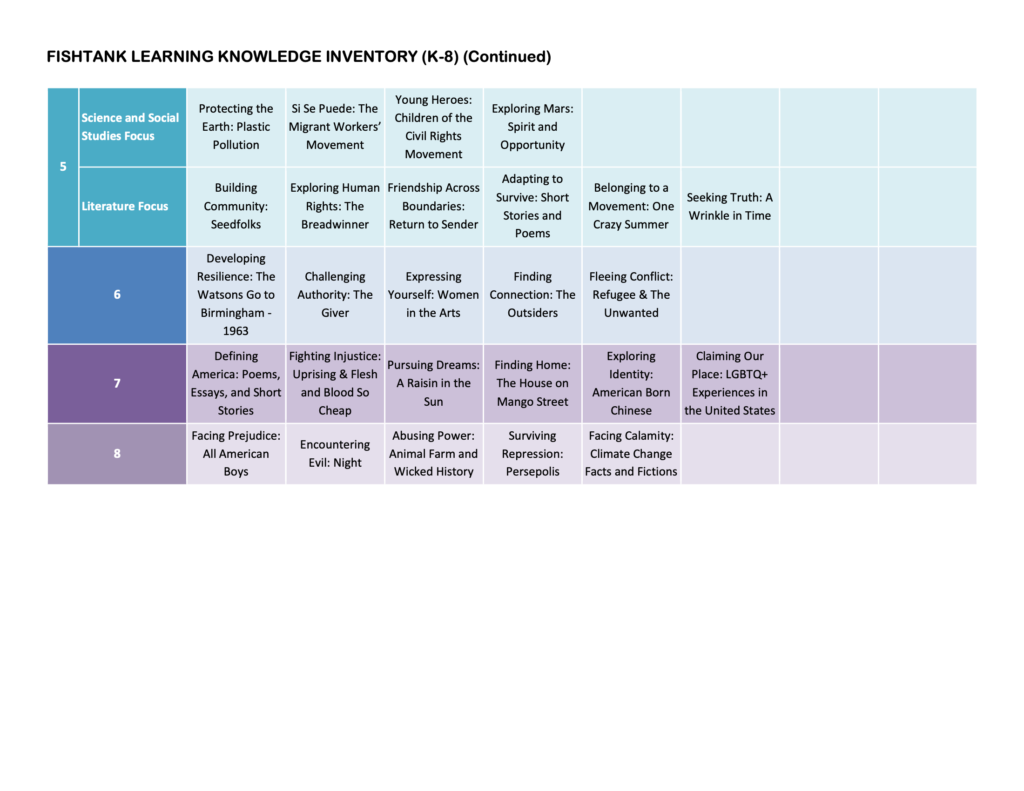

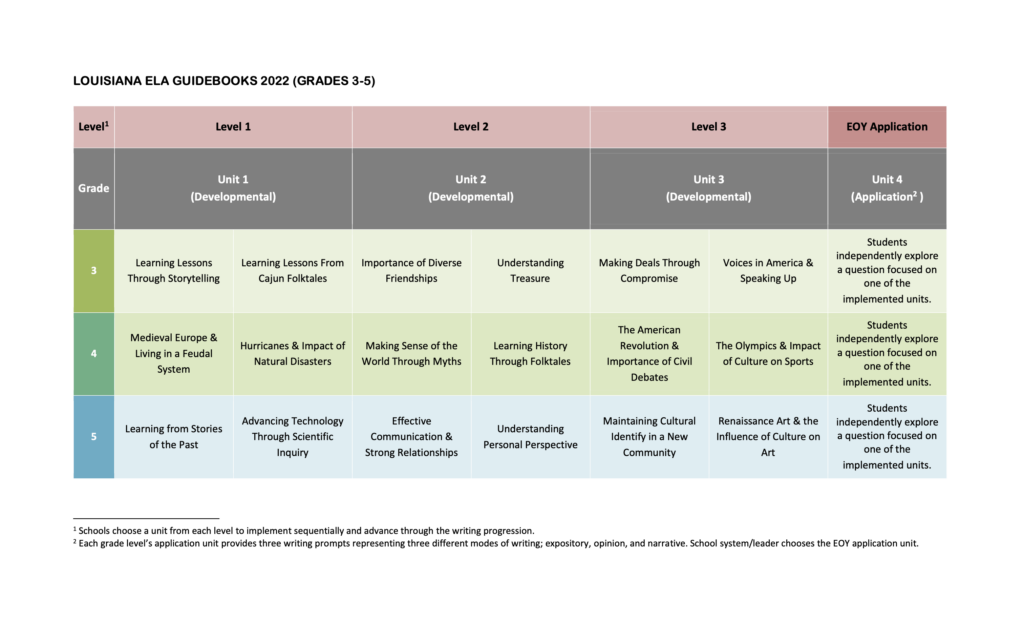

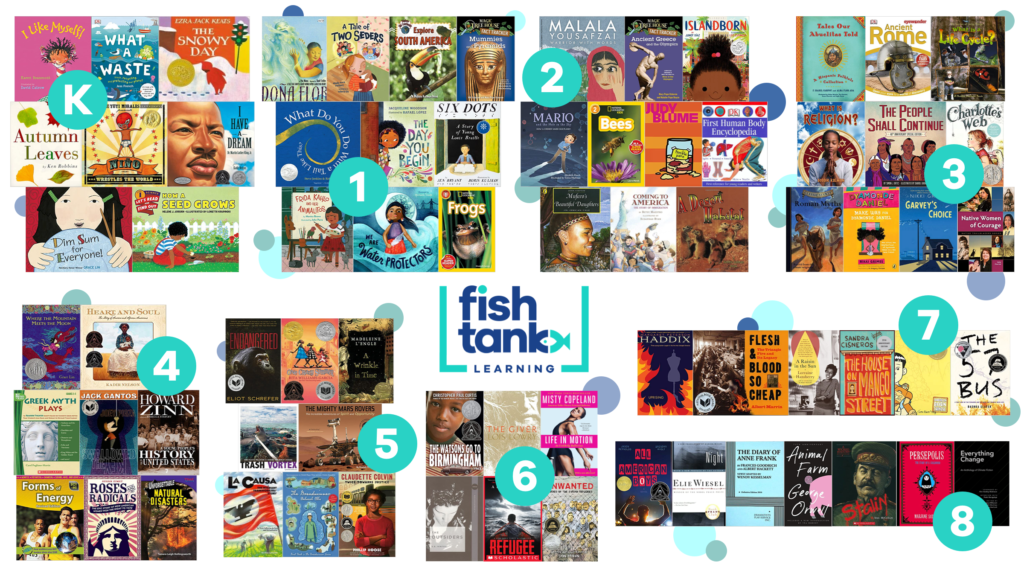

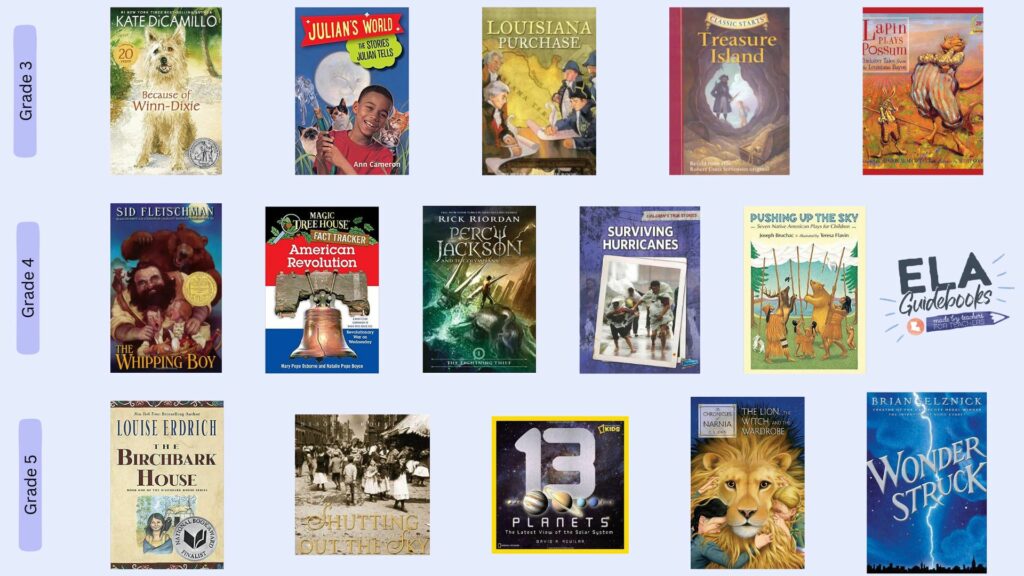

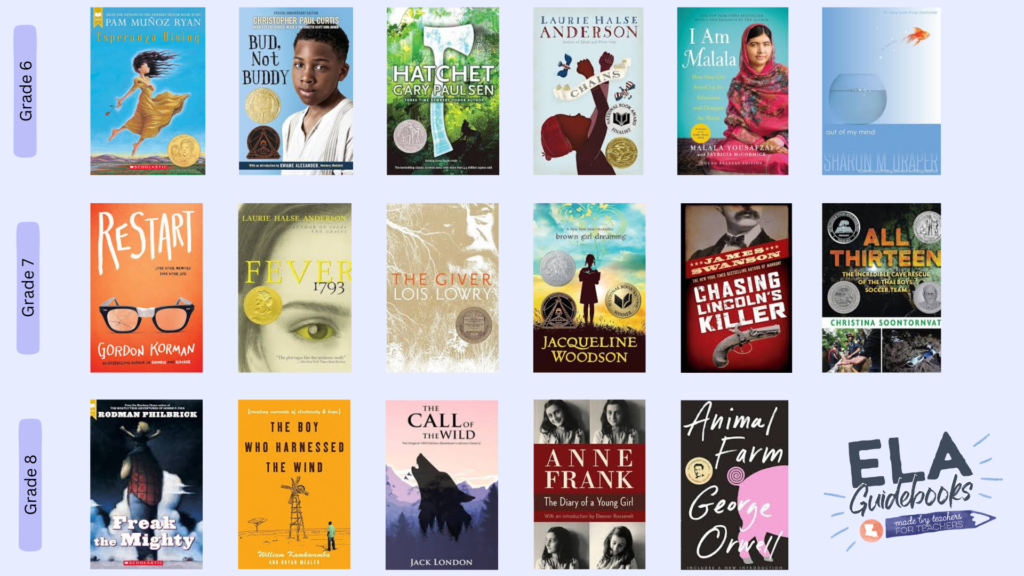

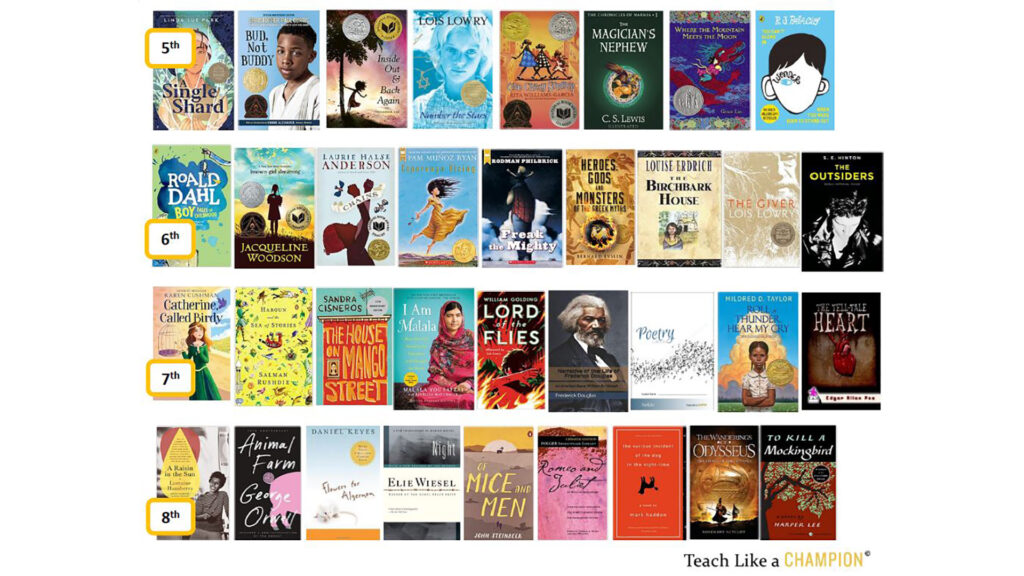

Explore the topics of study in knowledge-building curriculum:

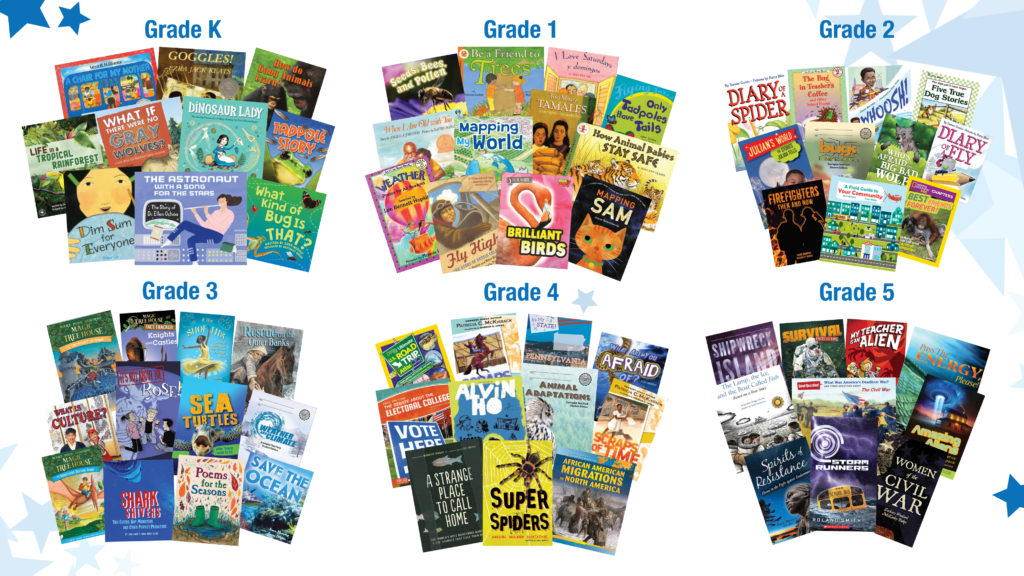

Each is carefully designed to ensure that students build a breadth of knowledge across grades, while also “spiraling,” bringing students back to topic areas (e.g., animal study) in which they can apply prior learning.

One important note about content: while there is long-standing science about the importance of knowledge to reading proficiency, there is no research showing what knowledge yields greater results. We hope this website will be used by school districts and parents to help choose curricula that best suit their community’s needs. Fortunately, a growing number of options are available.

Equipping students with reading skills to succeed as “knowledge-seekers”

Knowledge-building curricula develop reading, writing, thinking, and speaking muscles, putting students in the driver’s seat for future learning.

They take a research-based approach to literacy instruction, accounting for what is established through 500-plus research studies about how children best learn to read, write, think, and use language capably and with confidence. Most notably, they combine coherent progressions of thought-provoking content knowledge in powerful and proven ways with the other two essential science of reading ingredients well established in the literature:

- Systematic foundational skills instruction, including for older students who need it.

- Regular close reading of challenging, engaging texts that emphasizes how to learn independently from these texts.

These two must work in concert with building content knowledge to genuinely accelerate student literacy.

Foundational skills:

Research-based foundational skills programs rely on well-structured routines to teach children the code of the English language in a coherent sequence. In doing so, they turn young students into fluent readers so their attention can focus fully on the ideas and information being transmitted. Older students with unfinished learning—whether with reading fluency or specific decoding needs—are also served with care.

As students progress to reading text with richer ideas expressed in more profound ways, their knowledge and skills deepen. Along the way, they get the support they need to become capable and independent comprehenders of what they read.

Regular work with challenging texts:

These programs place complex texts (and thought) at the center of instruction via frequent close communal reading. Text selections allow students to both see themselves in what they’re reading and gain broad exposure to multiple perspectives and unfamiliar topics. Peer-to-peer discussions are threaded throughout the instruction to make classrooms vibrant centers of intellectual exchange and co-learning.

Lessons ask students to grapple with demanding questions about texts before teachers step in to provide support. This shifting of the work to students, while a ready-to-support teacher stands by, cultivates in students both the aptitude and the will to deepen their understanding of what authors say.

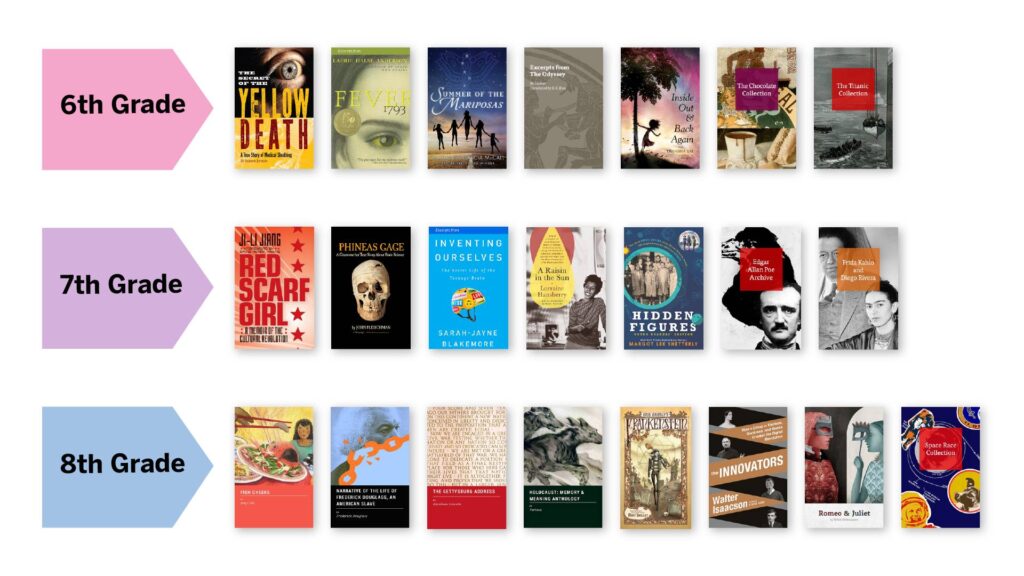

Rich, rigorous, diverse texts:

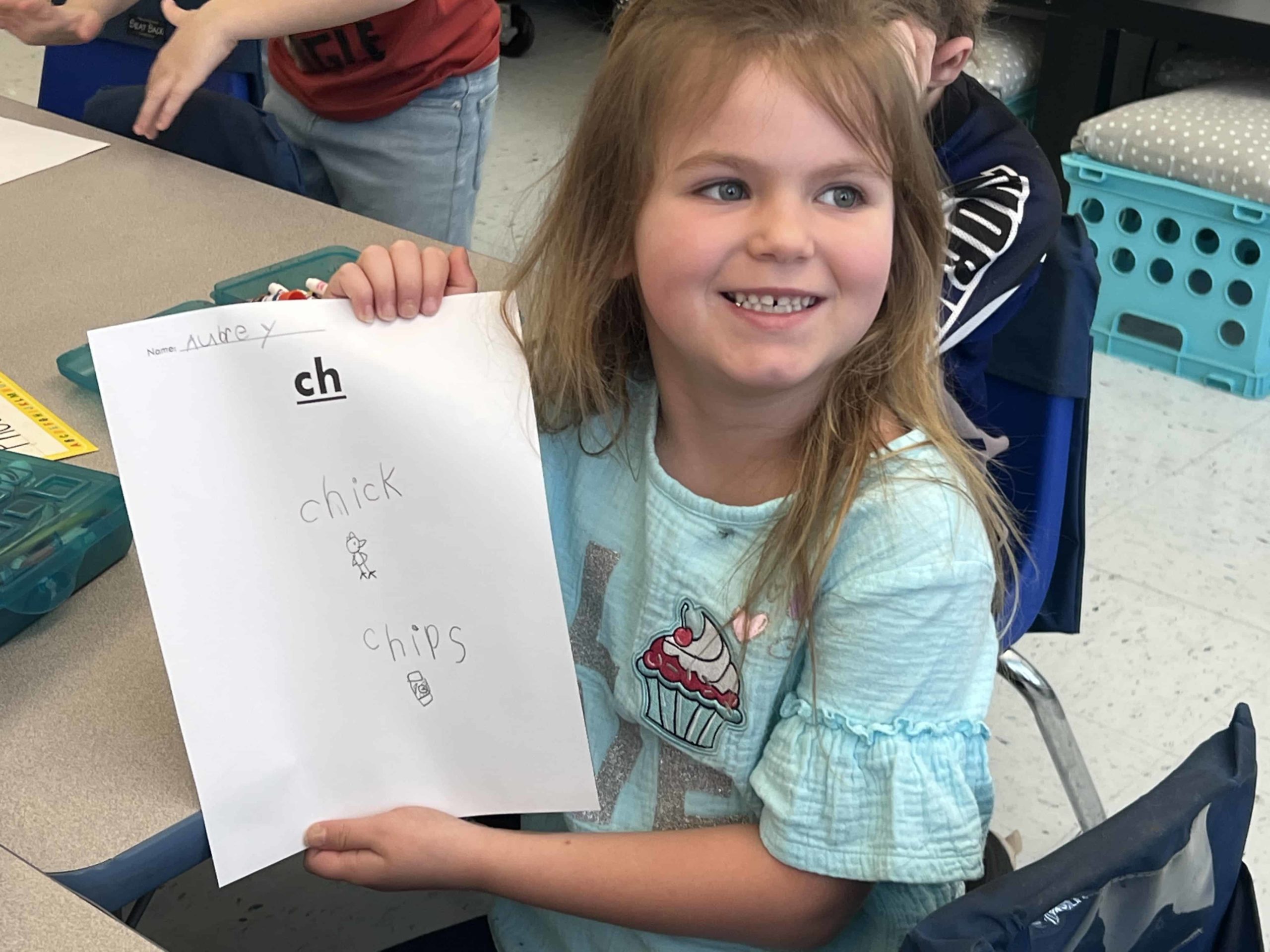

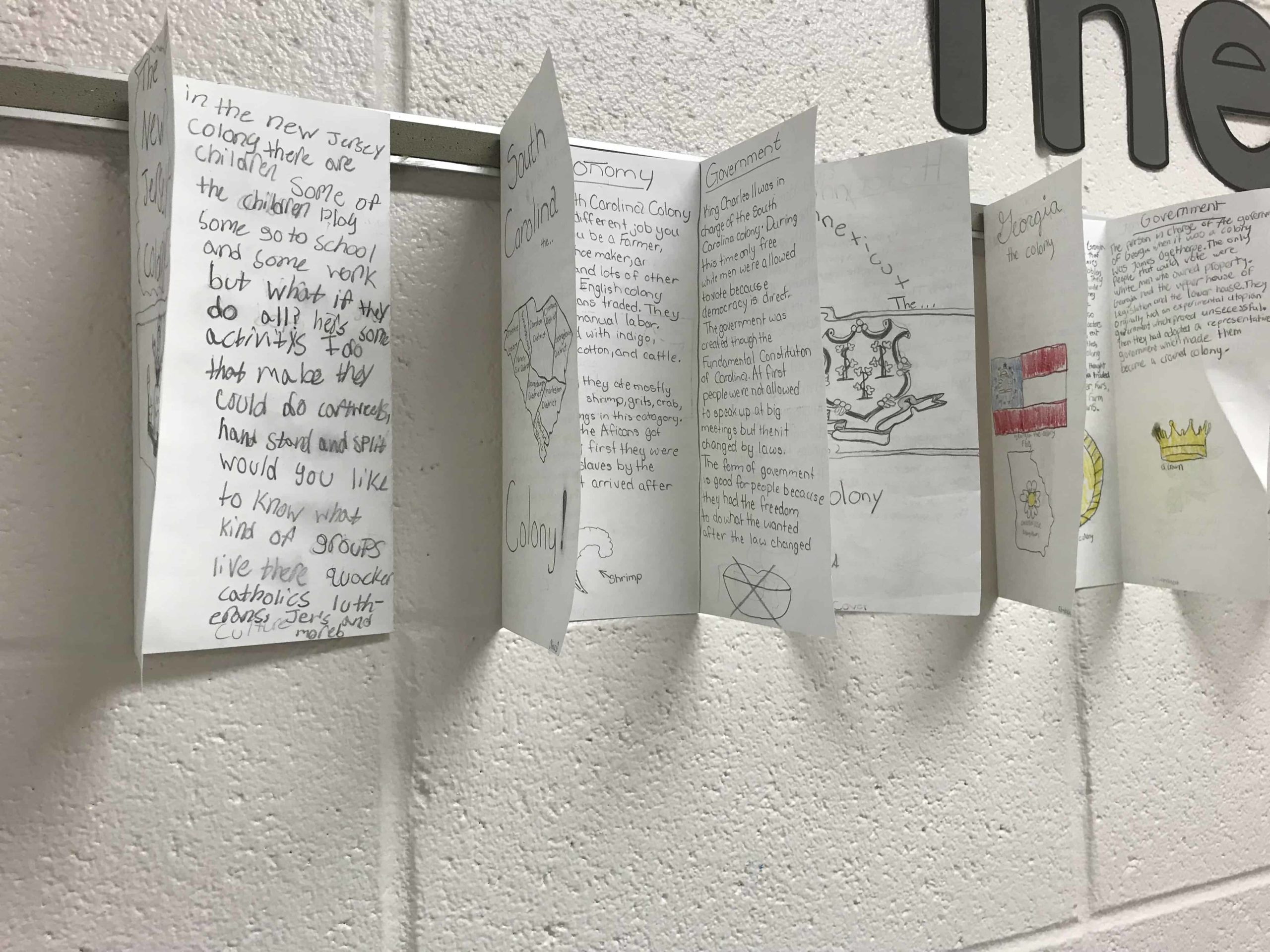

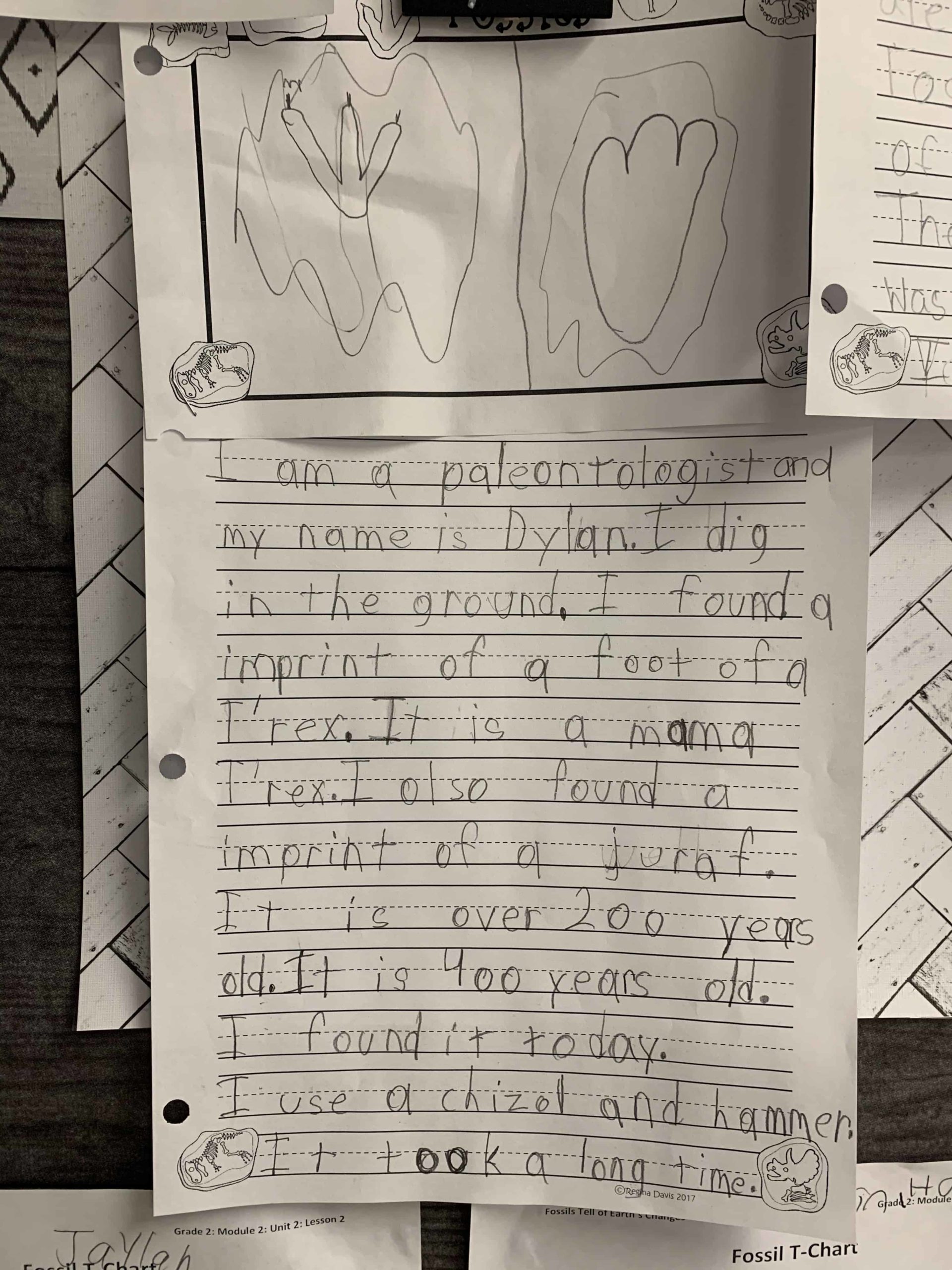

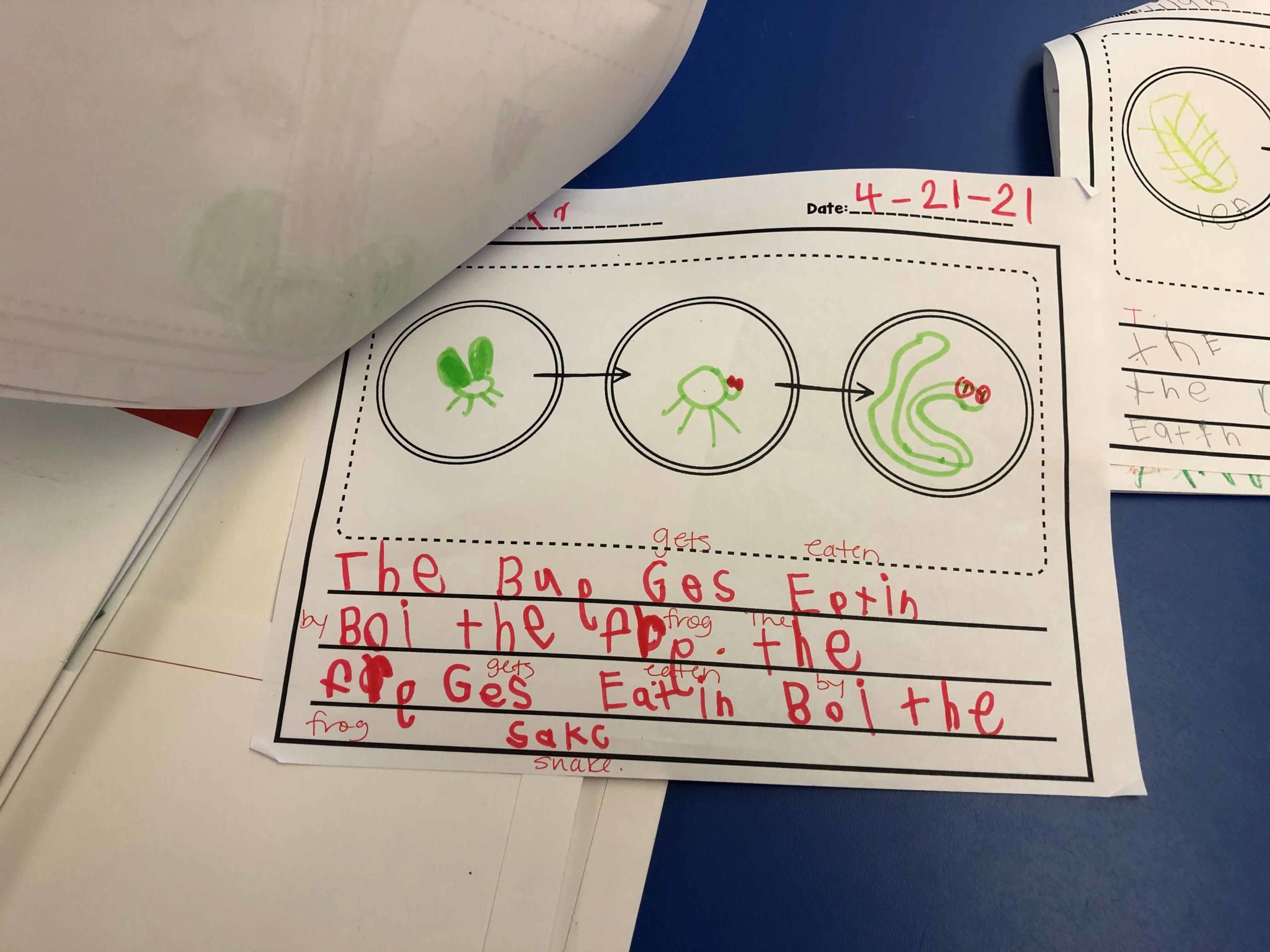

Student work tells the story

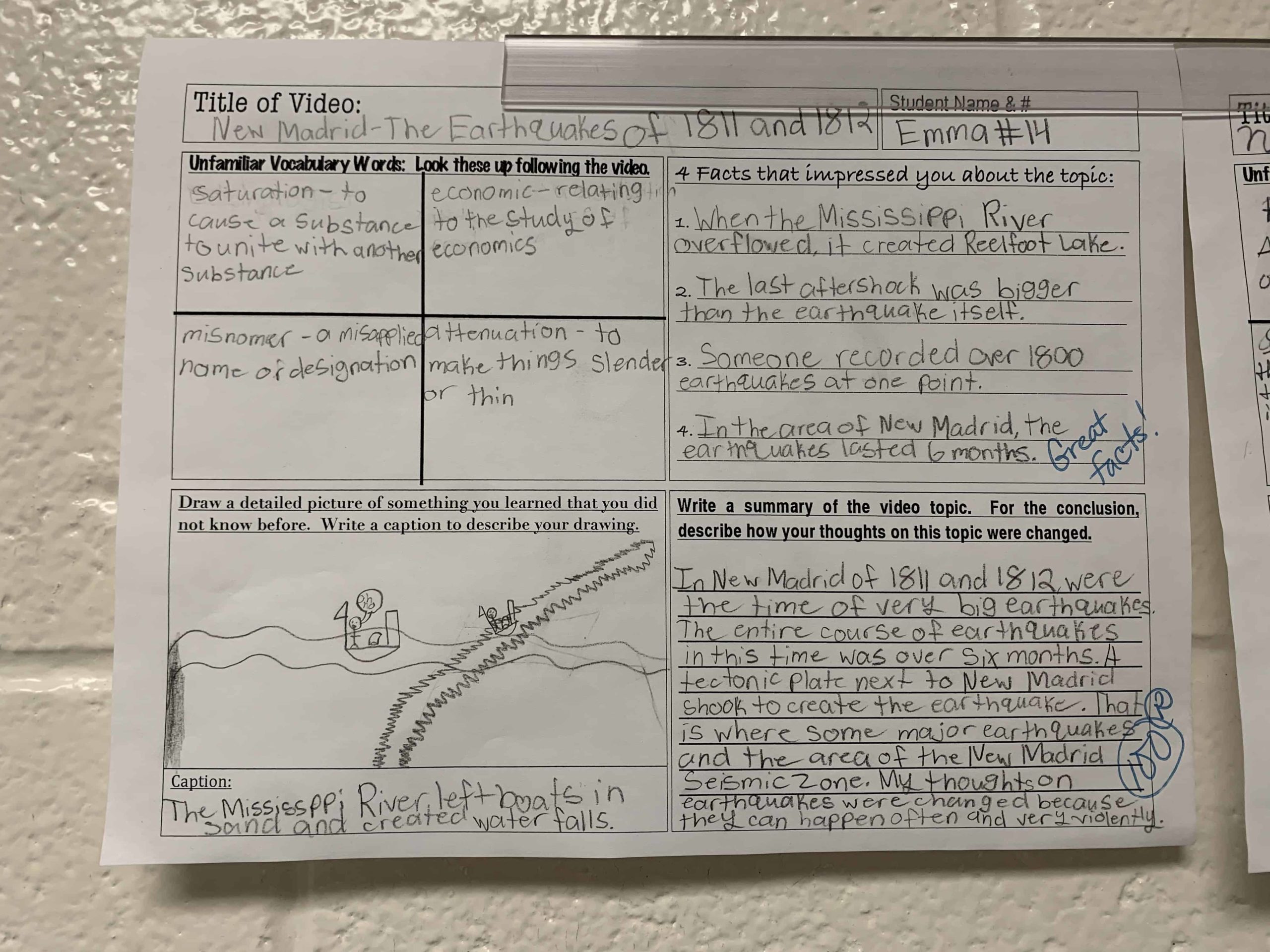

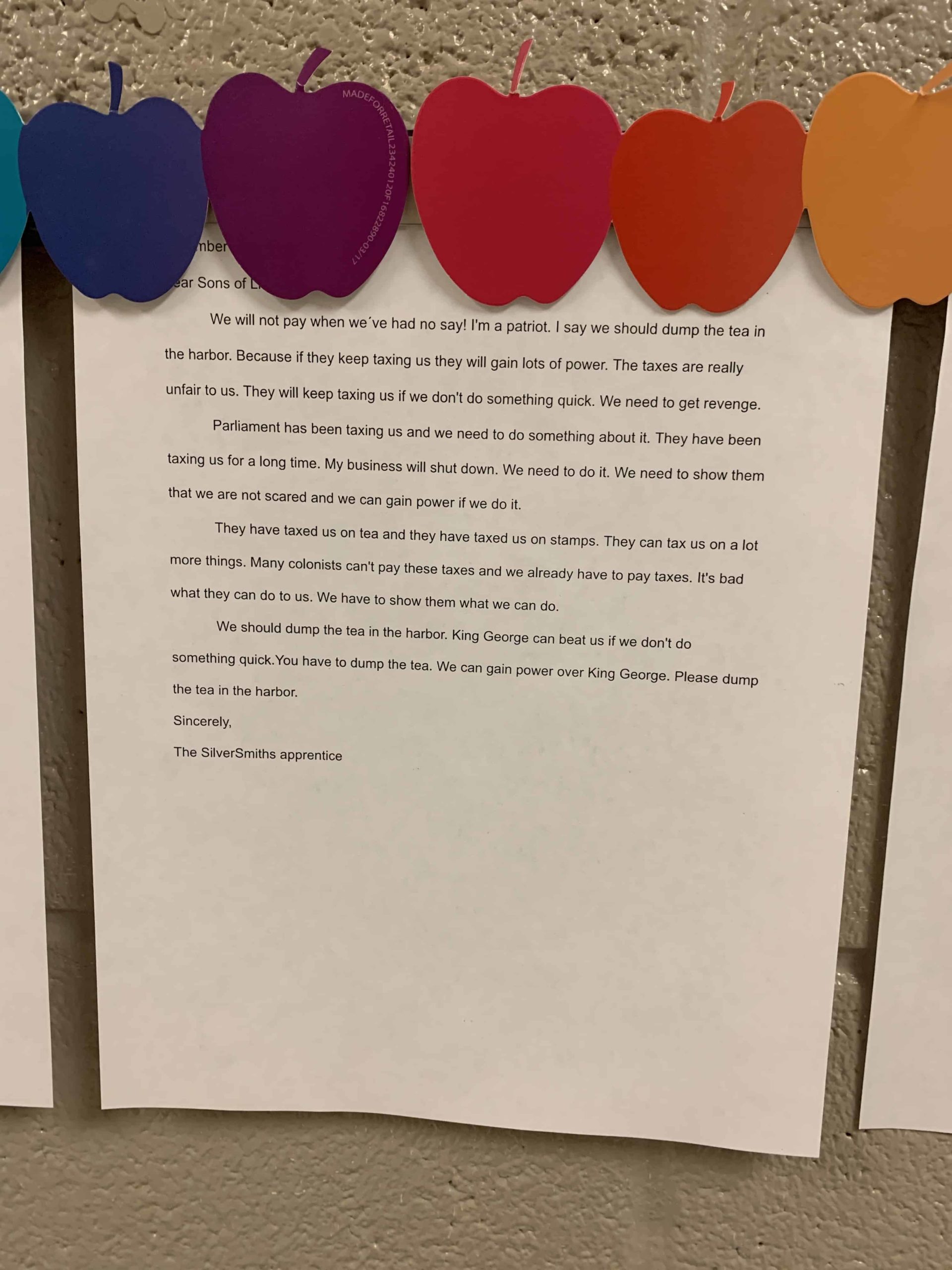

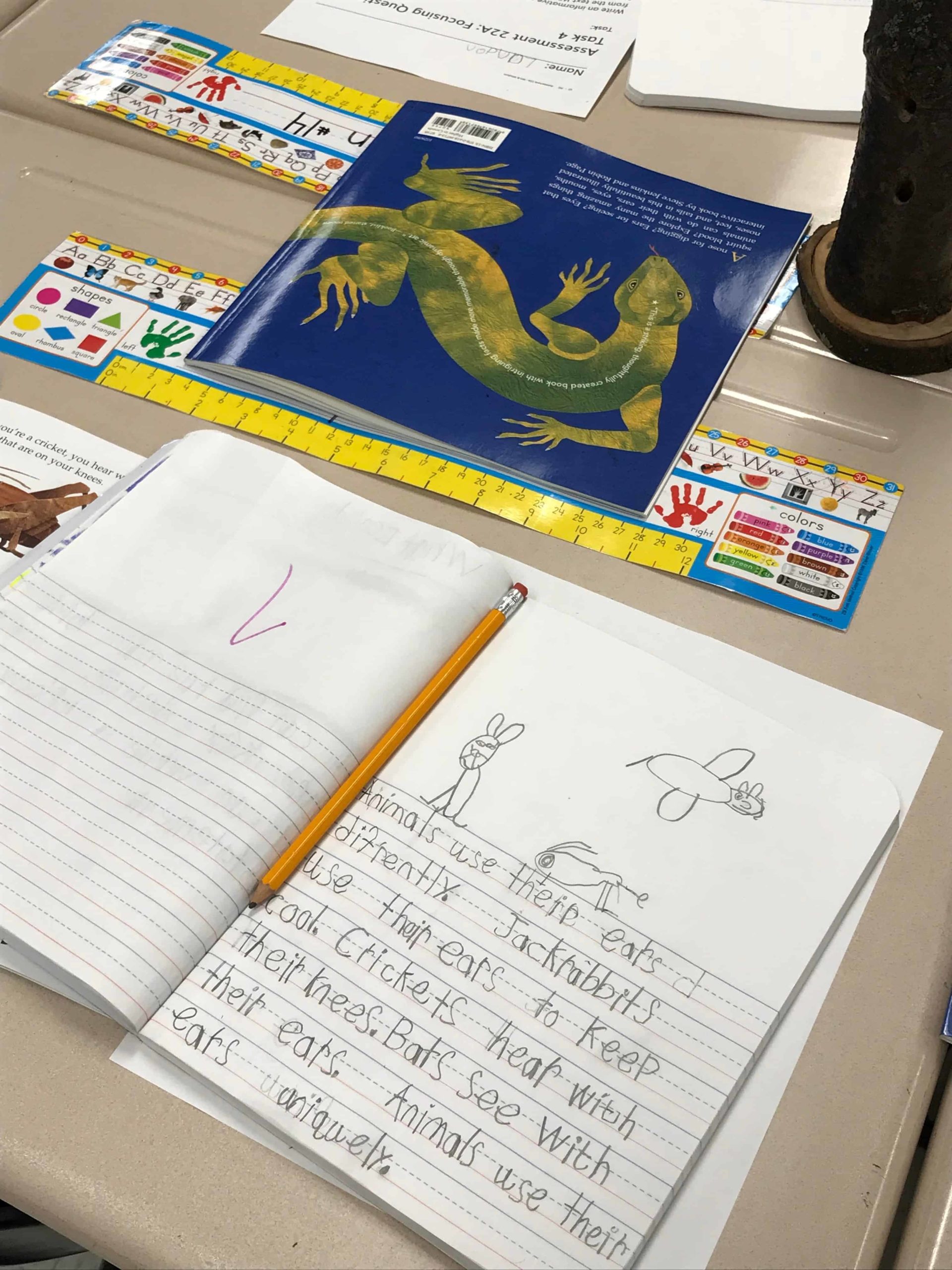

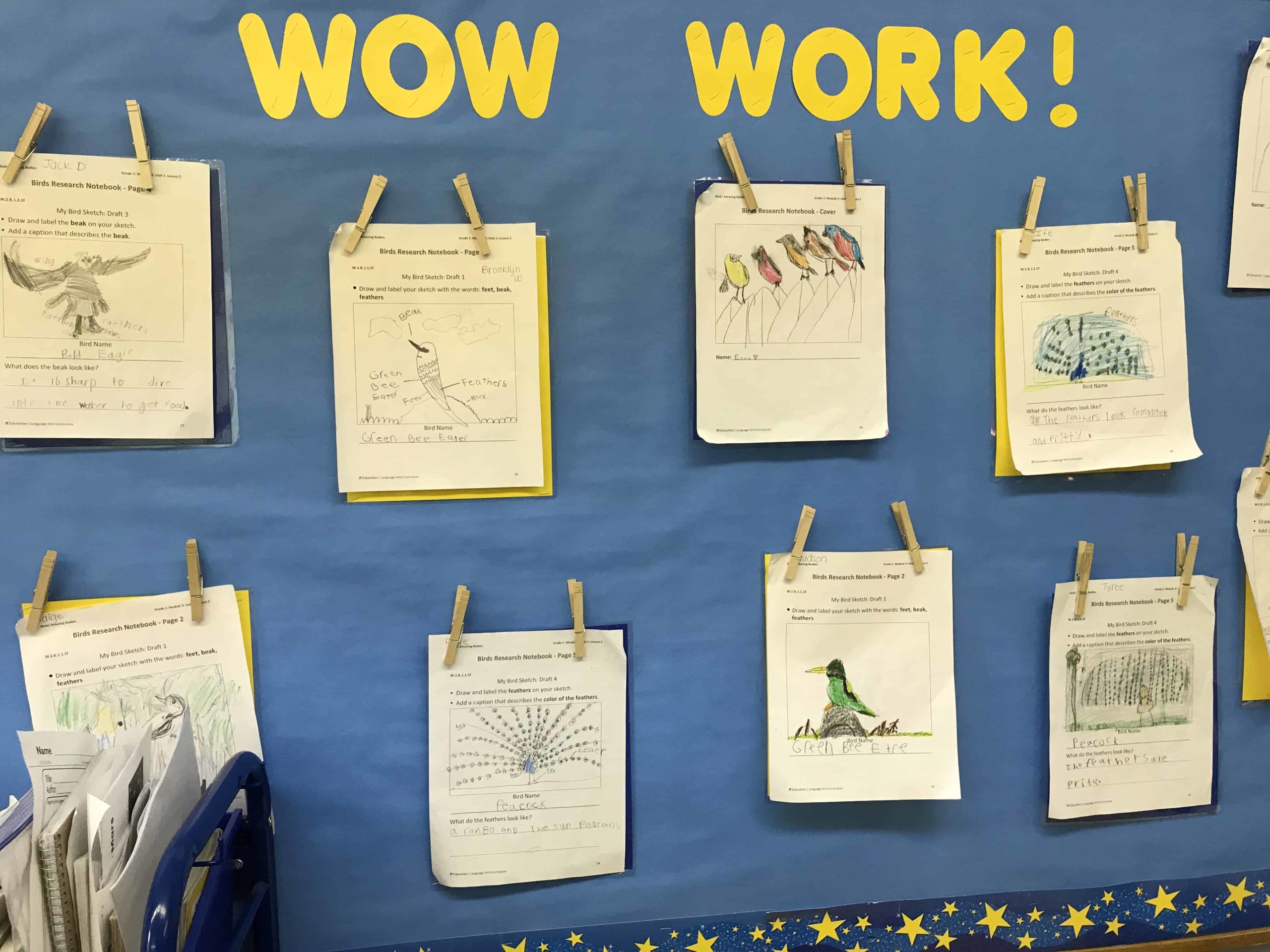

When we visit schools using knowledge-building curricula, we consistently hear educators raving about the quality of student work. Improved writing is one of the first changes teachers see. As one student told us, “Now I have something to write about!”

Writing from classrooms using knowledge-building curricula:

Implementation considerations

Implementation of a high-quality instructional program is a journey. There are no shortcuts to doing it right. There is a hearts-and-minds aspect to setting aside old ways of instruction so that teachers can move forward together to make real progress for their students, and it can not be ignored. Schools and systems that successfully implement new knowledge-rich programs prioritize the professional learning journey every bit as much as they do the decision about which curriculum to adopt.

Knowledge-building curricula are “educative” because in implementing them, and learning about all aspects of the science of reading while doing so, educators actually become better at their craft. Furthermore, teachers enjoy working with full-length texts, diving into topics alongside their students, and learning what excites them and how to engage them in growing their knowledge.

Educators who have recently implemented a knowledge-building curriculum frequently tell us that the process of implementing a new, rigorous curriculum is challenging, yet also deeply rewarding. Seeing far more students excel is inspiring, and teachers talk of falling back in love with their profession and appreciating how “all the pieces have come together.”