March 3, 2021 — Kenyatta Graves

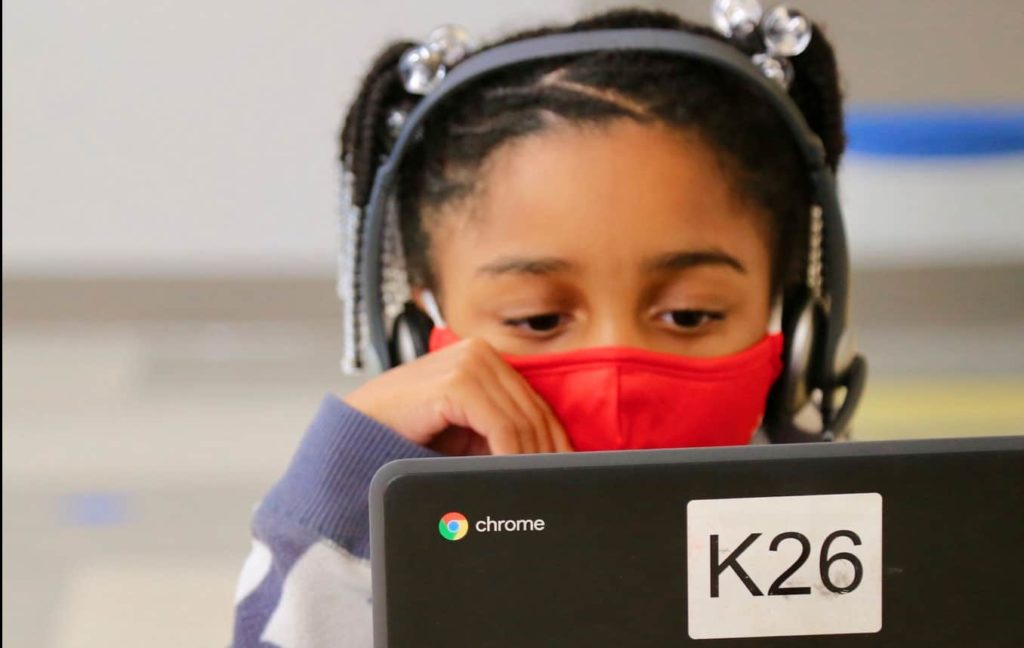

Over the past two weeks, I had the pleasure of joining the Knowledge Matters School Tour – Virtual Edition – for a visit to three schools in the Baltimore City Public School System. As the date approached, I became worried that an upcoming snowstorm might derail our plans. But, alas, that was Pre-COVID thinking, and by and large, snow days are a thing of the past. Technology allowed the tour to proceed without delay!

It was, of course, completely coincidental that on this cold, February day, our first lesson saw students discussing the properties and characteristics of wind. The lesson began with an essential question appearing on laptop and tablet screens: “How do people respond to the powerful force of the wind?”

Rodrick Johnson, teacher of this first-grade class and caretaker of what is known as “The Johnson Experience,” displays a copy of the poem, “The Wind” by James Reeves. He uses his digital tools to mark the text and guide an oral reading, indicating where the student he has called on should stop and where she should modulate her voice. After she reads the poem, the discussion begins about what the students notice and wonder.

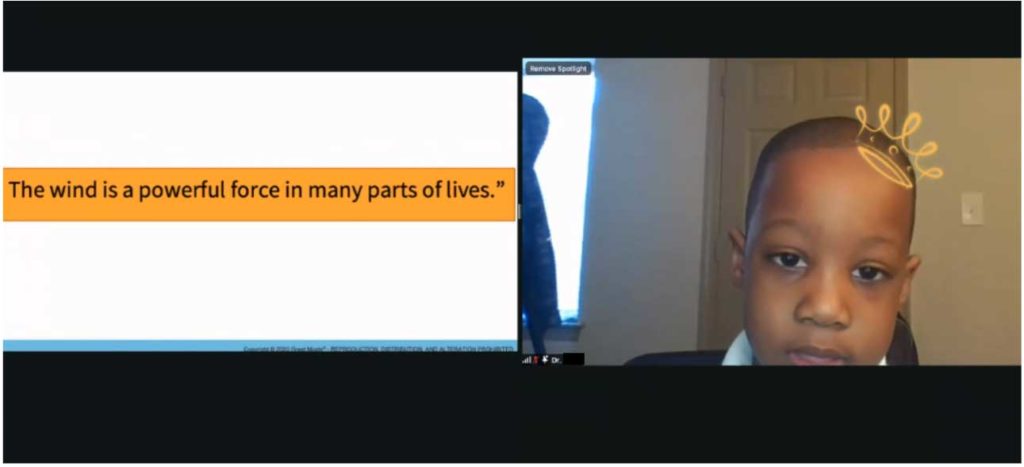

“Anyone else want to submit their opinion? How about you, Dr. C—?” Johnson prompts. (All students in Mr. Johnson’s class are addressed by affirming nicknames.)

Dr. C— responds with prior knowledge he possesses about tornadoes. Johnson encourages him to connect that to the poem itself, after which Dr. C— clarifies the specific line from the poem that supports the tornado observation.

Another student, called Madame President, shares: “I wonder what he is talking about when it says, ‘or steal through a garden and not wake the flowers’?”

“Thank you for submitting your wondering,” Johnson replies.

As someone who has observed hundreds of elementary school lessons over the years, I was struck by the cumulative quality of these future doctors and world leaders’ responses to this poem. Some were essentially text citations. Others evinced reflections resulting from connections to books previously read, including an informational text that introduced students to the observable properties of wind and the force it sometimes produces. An observation here led to a question there that circled back to a prior text that led to another question and another observation. While the content of Johnson’s virtual lesson is solidly identifiable in science standards and content, this lesson was happening during these first graders’ literacy block!

Baltimore City Schools is in its third year of implementing an English language arts curriculum called Wit & Wisdom throughout its K-8 schools. This has been an “all-hands-on-deck” effort, led by CEO Dr. Sonja Santelises, and involving teachers, coaches, building and district administrators, and families. It is an experiment in wholesale adoption of a knowledge-building curriculum that is being watched around the country.

Principal Samuel Rather called the content build “the bee’s knees.” “In my 4th grade classrooms, I learned so much about the heart by walking around and talking to my students. Student engagement has really increased. They’re excited about the lessons and they’re sharing it with their parents.”

“Instead of a curriculum where you’re jumping topic to topic, [Wit & Wisdom] has allowed students to build confidence because we keep circling back to focus on the essential question – and familiar vocabulary shows up across different texts,” Jeniqua Moran, an instructional coach for the district, shared.

Throughout our tour (of 1st, 4th, and 8th grade classes,) I was struck by a deep comfort – on the part of students and teachers alike – in scrutinizing complex, grade-level (and sometimes well-beyond grade-level!) texts. Most impressive was that the texts were not the tried and true we’re used to seeing read in K-8 classrooms. They include literature, prose, and visual art and units require comparative analyses of topics, often expressed through rich discussion and writing tasks.

Baltimore City has moved beyond the arcane practice of matching students to books at their “just right” reading level or teaching stand-alone individual lessons. Their curriculum features connected, sequential lessons that build over a long period of time (there are only four units a year.) These units explore a topic in greater detail, greater depth, and greater complexity than is possible with isolated texts.

The familiarity of rituals and routines is also an important feature of the curriculum. Principal Benjamin Crandle described the systemic benefits of this familiarity when he said, “They can take on more themselves because they already know the processes and how to build on a structure they already understand. The student interactions and questioning are now familiar, and they take more of a leadership role in the lesson.”

The way students found nuance, message, and meaning in 4th and 8th grade classes, the ways those observations surfaced almost in predictable fashion, suggested that the District’s multi-year investment is already paying learning dividends. And if the expectations set by teachers like Mr. Johnson, at the very beginning of a student’s learning career, portend anything, Baltimore’s harvest may be abundant in the years ahead.

(Our second installment of the Baltimore City School Tour – Virtual Edition blog, where we visit 4th and 8th grade classrooms, appears in Part 2.)