March 8, 2021 — Kenyatta Graves

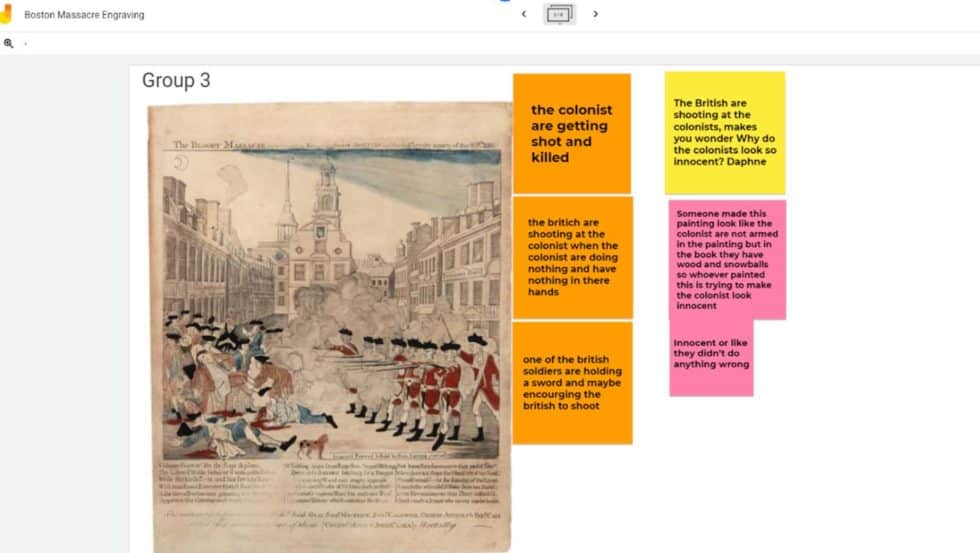

Katie Scotti’s fourth-grade class is immersed in studying the details of the Boston Massacre by analyzing Paul Revere’s famous engraving of that incident. The lesson, part of the Wit & Wisdom English language arts curriculum adopted by Baltimore City Public Schools, encourages students to consider both sides of the conflict, British and colonist, prior to writing an explanatory essay. It occurs early in a unit that also features the book George vs. George: The American Revolution as Seen from Both Sides by Rosalyn Schanzer.

Virtual “Notice and Wonders” by Baltimore 4th graders about Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre:

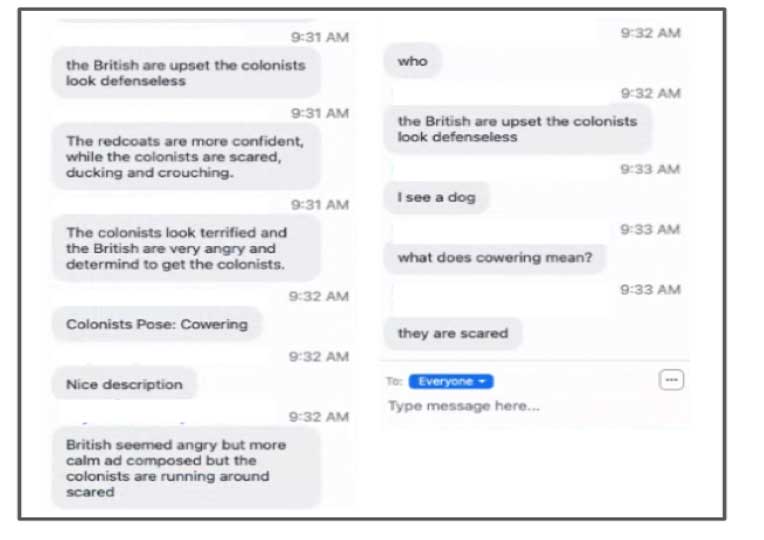

Experiencing this lesson in the virtual format, with young faces filling the screen like the opening credits of The Brady Bunch, was a unique experience. We were able to witness how individual student contributions triggered heads tilting left or right to some new focal point talking on the screen. Amazingly, the students are really speaking to and with each other as the lesson asks them to assess color, light and shadow, lines, shapes, and texture – all while Ms. Scotti is drawing out observations about abstract notions like perspective, outrage, and loyalty, using knowledge students have been building about the American Revolution so far in the unit.

Scotti is masterful at the digital tools at her disposal, artfully moving students from whole class instruction, to breakout room small groups, to collaborative tools that capture student shares, all while never missing questions and comments that fill the chat feature of the platform. I admit I missed the crowd or collective energy which felts absent, as there are no moments in virtual space where students mutually, instantly, express agreement with a peer’s response, no excited, simultaneous utterances that sometimes surge a classroom to some new electric moment. Yet Scotti has found a way to surface peer-to-peer engagement online, seemingly refusing to forego the written lesson’s penchant for deeper discussion, the opportunity for students to pause and test, to exercise a new notion.

As students age through Baltimore’s implementation of the Wit & Wisdom curriculum, it was gratifying to see the lessons maintain a recognizable format, even as the expectations swelled. The notice and wonder routine present in the 1st grade lesson about the wind was here as well. Teachers credited the familiarity of these routines with helping them bridge to virtual instruction. According to Katie Meath, an academic content liaison for the district, having these instructional routines reappear year to year “is sort of like that Velcro for them.” Janise Lane, Executive Director of Teaching and Learning for the district, said that the familiarity of the routines is part of what empower the kids to “do the actual work of the knowledge build.”

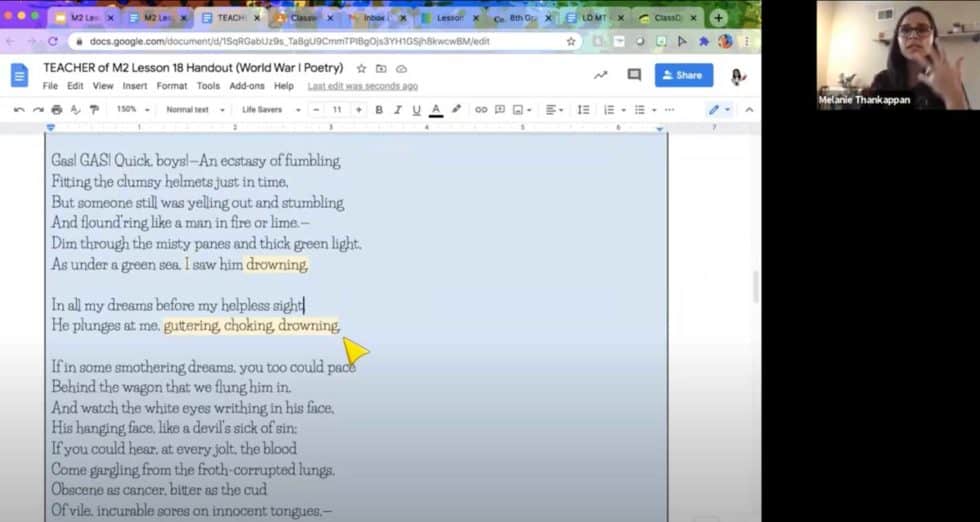

In Melanie Thankappan’s eighth-grade class, students are responding to poetry and artwork that offer insight into the soldiers’ physical and emotional experiences during World War I. Once again, students are using visual art in a comparative analysis with literary art. While 4th graders scrutinized a painting with clear, concrete images, 8th graders are asked to use the same “close reading” strategies to identify the subject of an abstract painting – (Soldiers Playing Cards by Fernand Leger) and explain how it amplifies the perspectives of fallen soldiers in the poems.

Fernando, one of 50+ students in the online class, makes effortless inferences: “It looks like a maze that mostly you’d get lost in. The arms and the cards and everything. It just reminds me of a maze.” Fernando’s insight is also a reference to the unit’s anchor text, All Quiet on the Western Front.

The lesson we observed asked students to compare and contrast the poems, “In Flanders Field” by John McCrae and “Dulce et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen, both texts that many college students struggle to analyze effectively. Some share their questions and observations orally with the class; others post their reactions in the class chat. Many of the students’ responses are highly advanced, including Moussa’s who offered, “I thought about it like a message to generations that they must now carry a torch. They’re carrying on the duties of those that have died in World War I. They sacrificed their lives.”

Thankappan teaches much like an engineer, deftly moving multiple trains through a chokepoint in travel. Some smoking engines of knowledge, she pulls forward. Others she places in queue to await their turn in the virtual space. Not once does she call on a student who is unready to speak and share.

Shortly after Thankappan’s class concluded, my colleagues and I visited with a panel of students and asked them to describe their experiences inside this classroom and inside this curriculum. Several students noted that the opportunity to wrestle with such sophisticated texts inflated their confidence and made them approach challenging academic tasks with greater degrees of comfort. One young man noted that it mattered to him that his teacher expected that he had the skills necessary to “tackle the harder books and poems.”

In our debrief with her, Dr. Santelises was pleased to hear about the students’ reactions. “I am very big on the long-term impact [for students],” she said. “Children of color, children who are newly arrived in the United States, children who come from economically under-resourced communities – need to have and feel the power of being able to tap into the collective knowledge-base that drives academic success in this country—as well as the knowledge of how they, themselves, and their communities contribute to that larger narrative.

“And so the ability to be able to be in a room, be in a classroom, be in a discussion, and own the content of the American Revolution – and be able to connect to those who might have a more traditional view, and limited view of the American Revolution – and also to assert, ‘let me tell you something about the black folks who were in the American Revolution,’ ‘let me tell you something about how native Americans viewed this and how they splintered, in terms of their support,’…. That cumulative empowerment reinforces the idea that…you belong in the room. You’re not missing something. You don’t have holes in your knowledge. In a lot of ways, you have a fuller knowledge. Because you understand what the mainstream narrative has. And what the mainstream narrative is missing.”

“The most powerful teachers,” she later said, “are the ones who know how to use the content…to then allow students to make connections to themselves. It’s more than just text to text, text to self—that has its place. But it is about young people seeing their place in the larger global humanity.”

I am deeply grateful to have had the opportunity to see inside what’s happening in Baltimore City Schools and to speak with these amazing students, teachers, parents, and administrators. Their multi-year commitment to a knowledge-rich English language arts curriculum has the ability to substantively set national precedents.