As we heard in Episode 1, learning to read is about much more than being able to decode words. Remember the excerpt describing a cricket match?

Much depended on the two overnight batsmen. But this duo perished either side of lunch—the latter a little unfortunate to be adjudged leg-before—and with Andrew Symonds, too, being shown the dreaded finger off an inside edge, the inevitable beckoned, bar the pyrotechnics of Michael Clarke and the ninth wicket.

To be able to really read that paragraph you needed to be able to do much more than just decode: you also needed to comprehend it. Teachers spend hours every week trying to teach comprehension, but unfortunately the traditional approach often emphasizes skills and strategies, like “finding the main idea”, and practicing them on texts about random topics, as you heard from Deloris Fowler in the last episode.

In Episode 2, host Natalie Wexler and prominent reading researcher Dr. Hugh Catts delve into why the science of reading comprehension conflicts with this traditional approach. Dr. Catts, a professor of communication science and disorders at Florida State University, explains that reading comprehension is not a set of discrete skills that can be applied to any text. Instead, comprehension is deeply intertwined with the reader’s prior knowledge about the topic, their vocabulary, and their general knowledge.

You can see this for yourself if you apply a skill like “finding the main idea” to the cricket excerpt. Unless you know a bit about cricket, and your vocabulary includes both cricket-specific words like “wicket” and general vocabulary like “pyrotechnics,” you’re unlikely to be able to find the main idea–or even understand the paragraph. .

This principle was demonstrated in an experiment known as the “baseball study,” conducted by researchers Donna Recht and Lauren Leslie in the late 1980s. The study found that students who were “poor readers,” according to a standardized test, and also baseball experts had no trouble understanding a passage describing a baseball game–and in fact did better than “good readers” who knew little about baseball. Other studies have found similar results.

In this episode, Dr. Catts also shares how his own research has helped to reveal flaws in our standard approach to teaching and assessing comprehension. From 2010 – 2016, he was involved in an extensive and long-running research initiative launched by the U.S. Department of Education called Reading for Understanding. Over 130 researchers in six teams conducted research focused on improving students’ comprehension, at a cost of $113 million dollars. Hugh’s team designed a content-rich curriculum for kids in preschool through third grade, teaching them vocabulary, grammar, and domain-specific information over the course of a year. They also taught them how to do things like monitor their comprehension.

What they found was that “the kids learned what we taught,” Hugh says, but they showed no improvement on standardized comprehension tests. Hugh wasn’t surprised by this finding because he was aware of previous studies showing that comprehension skills are unlikely to transfer to new contexts. But unfortunately, that isn’t the message most teachers have been getting.

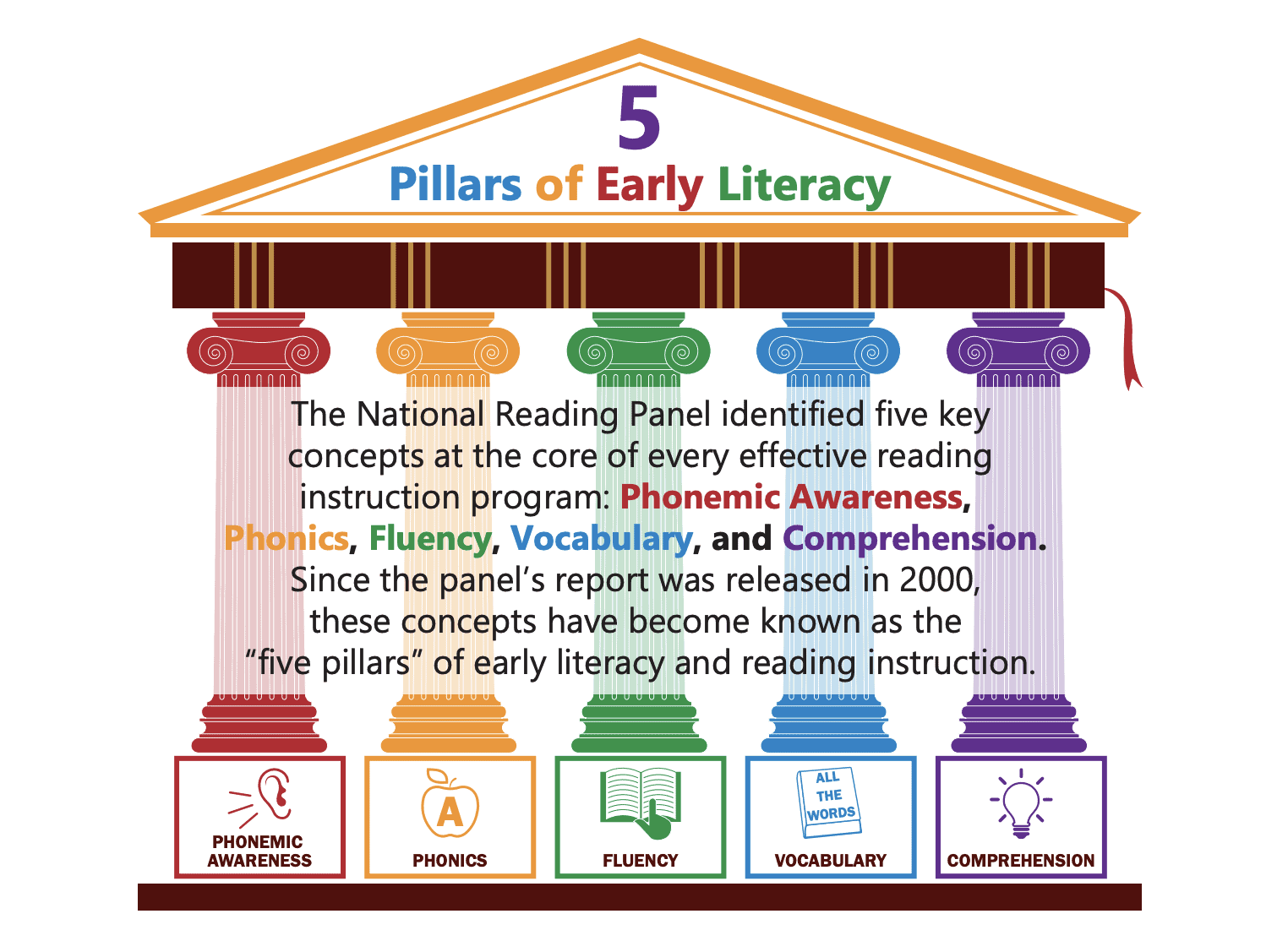

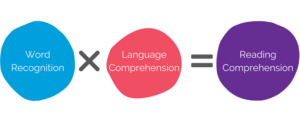

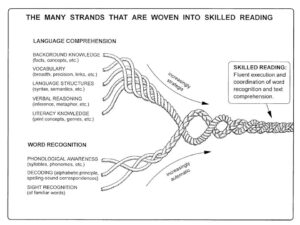

These are the three infographics Hugh and Natalie discuss during this episode; the Five Pillars of Literacy, The Simple View of Reading, and the Reading Rope, or Scarborough’s Rope:

Of these three, Hugh believes the Reading Rope does the best job of conveying the complexity of comprehension. However, Hugh says even the Reading Rope can give the mistaken impression that language comprehension should be approached like decoding instruction–as a set of skills to be mastered rather than a complex process that is highly dependent on knowledge.

Fortunately, there are increasing numbers of knowledge-building curricula that put rich content in the foreground rather than trying to teach comprehension skills as an end in themselves. At the same time, many schools continue to teach comprehension in a way that holds some students back.

In the next episode, Natalie will speak with three teachers who have made the switch to using a knowledge-building curriculum. They will share their experiences and the changes they have seen in their students’ comprehension and engagement. Stay tuned for more insights into the science of reading comprehension and the importance of knowledge-building in literacy instruction.

Episode Transcript

Hugh Catts

One of the reasons that we focused on strategies so much is that we’ve thought about reading as if it was a set of skills that you use when you encounter a particular text, and that we can go from one particular text to the next using those particular skills. But reading comprehension doesn’t work like that. It’s not a set of skills, that domain independent that you can use when you encounter any particular texts.

Natalie Wexler

Welcome to Episode Two of the knowledge matters Podcast. I’m Natalie Wexler. In this episode, we’ll look at what cognitive science the science of learning can tell us about how reading comprehension works. And we’ll look at how the standard approach to teaching reading comprehension conflicts with what science tells us.

The voice you heard a moment ago was Hugh Catts, a professor of Communication Science and disorders at Florida State University and a prominent reading researcher. We’ll be hearing more from him soon. If you’re a teacher, what you’ll hear in this episode is probably very different from what you learned about reading comprehension during your training, and from what your curriculum tells you about how to teach it.

In Episode One, we talked about how the standard approach to comprehension is to see it as a set of skills and strategies like finding the main idea that needs to be taught directly. There’s often a skill of the week which kids practice on texts on random topics that have been determined to be at their individual reading levels.

Here’s the theory that approach is based on: eventually kids will master the skills and be able to use them to understand any text they read in the future. In other words, the assumption is that comprehension is domain independent as Hugh Catts put it, but remember that paragraph we heard in the first episode describing a cricket match:

Male Voice

Much depended on the two overnight batsmen, but this duo perished either side of lunch, the latter a little unfortunate to be adjudged leg-before…

Natalie Wexler

Some people argue that it’s not important to teach kids factual information because they can just google it. But I tried googling all the cricket terms I didn’t understand in that one paragraph. It took me at least 45 minutes. And I still couldn’t understand the paragraph. I couldn’t understand the definitions. Because I don’t know enough about the domain of cricket.

It’s a lot easier to understand a text if you already have background knowledge about the topic than if you have to look up a lot of the words. That’s something cognitive scientists have known about for quite a while now.

Here’s another paragraph:

Male Voice

Churniak swings and hits a slow bouncing ball toward the shortstop. Haley comes in, fields it and throws the first but too late. Churniak is on first with a single, Johnson stayed on third. The next batter is Whitcomb, the Cougars’ left fielder.

Natalie Wexler

If you’re a baseball fan, you can understand that paragraph, no problem. But it’s probably not because you have great comprehension skills.

Back in the late 1980s, a couple of researchers Donna wrecked and Lauren Leslie decided to conduct an experiment that has come to be known as the baseball study. They wanted to know what was more important to reading comprehension, general skills, like finding the main idea, or how much the reader knows about the topic.

Their research subjects were seventh and eighth graders. And they chose the topic of baseball because they figured there were a lot of kids out there who weren’t generally good readers, but did know a lot about baseball. They divided the kids into four groups, depending on how well they scored on a standardized reading comprehension test, and how much they knew about baseball.

Then they gave them all a passage to read describing a baseball game. That paragraph you heard was from the beginning of it, and tested their comprehension of that passage. Here’s what they found. What really made the difference was how much a kid knew about baseball. The kids who were poor readers, according to the test, and were also baseball experts did quite well. In fact, they did a lot better than the good readers who knew very little about baseball.

The same kind of study has been done in other contexts, and the same result has always been found. Knowledge of the topic is more important than general reading comprehension skills. That may be obvious when we’re talking about a subject with its own special lingo, like cricket or baseball or you know molecular biology. If you know the lingo, it’s easier to understand a text on that topic.

What may be less obvious is how much we rely on our general knowledge to understand everything we read. That’s especially true of academic knowledge. If you know the answer to a question like in what part of the body does pneumonia occur, you’re likely to have good general reading comprehension. When you come across a term like pneumonia, you don’t have to think about what it means or look it up. That enables you to pay more attention to the meaning of whatever you’re reading. And there’s a third layer of knowledge that’s crucial to reading comprehension. In addition to knowledge of the topic in general academic knowledge, knowledge of syntax, or sentence structure.

Written language uses more complex syntax than spoken language. So a student might be able to carry on a conversation without any difficulty, but still struggle with reading comprehension and with writing. Even children’s books use more complex vocabulary and syntax than adult conversation. Here’s a paragraph from the popular children’s book Stellaluna.

Male Voice

One night, as Mother Bat followed the heavy scent of ripe fruit, an owl spied her. On silent wings the powerful bird swooped down upon the bats. Dodging and shrieking, Mother Bat tried to escape, but the owl struck again and again, knocking Stellaluna into the air. Her baby wings are as limp and useless as wet paper.

Natalie Wexler

That’s not the way most of us talk. We don’t tend to use words like sent and spied and we don’t usually begin our spoken sentences with a phrase like dodging and shrieking.

This is one reason it’s so important to read aloud to children from books, they can’t yet read themselves. It helps build their vocabulary and their familiarity with complex syntax.

Many scientists have studied the role that knowledge plays in reading comprehension. But there’s also a lot of reading comprehension research that has basically ignored knowledge. That is, treated comprehension as though it were just a set of skills and strategies. And that skill and strategy research is what has helped shape the standard approach to literacy instruction. While the research on knowledge has generally been overlooked. Why is that?

Let’s go back to Hugh Catts, the professor at Florida State.

Hugh Catts

I initially got interested in reading because of a family history of dyslexia. I have a brother who’s dyslexic and I had difficulties learning to read when I was a young child. And much of the research that was coming out talked about the language basis of reading and reading problems. And it was quite relevant because the problems they were talking about were the ones that we experienced in my family. And I knew them firsthand.

Natalie Wexler

Hugh started out studying kids who, like his brother and himself, had problems hearing and retrieving the sounds in individual words, something that is often called phonological or phonemic awareness, and how those problems were connected to reading difficulties. But he started following those kids as they got older, and he began to look at their reading comprehension.

Hugh Catts

We’re particularly interested in children that had adequate word reading but difficulties in comprehension, sometimes known as poor comprehenders.

Natalie Wexler

Eventually, that led to his involvement in a big research initiative called reading for understanding, which focused on improving students comprehension. It was launched by the US Department of Education in 2010. And it lasted six years, there were six research teams with a total of over 130 researchers. The initiative cost $113 million. Hugh’s team designed a content rich curriculum for kids in preschool through third grade.

Hugh Catts

So we taught them vocabulary, we taught them grammar, taught them text-level information within a content area, as well as what we call higher level language skills such as inferencing, and comprehension monitoring. And we did that for about a year or so. And when we were done, what we found was that the kids learned what we taught. They learned the vocabulary, they learned the grammar. They could, they could monitor their comprehension. They did a little bit better in text structure, understanding text structure, but what didn’t change was their ability on comfort on tests, standardized tests of comprehension.

Natalie Wexler

It wasn’t just Hugh’s team that had that experience

Hugh Catts

Several other teams had used somewhat different interventions to try to improve reading comprehension. And they basically found the same thing that we did that you could change what we refer to as proximal measures. That is, the things that you’re actually taught. But a distal measure – like a standardized test or reading comprehension – either didn’t change at all, or you got a very small change in that measure.

Natalie Wexler

Most scientists see those standardized tests as the best way to measure whether the thing that they’re trying, the intervention, has worked. But remember, the reading passages on a standardized test aren’t related to anything kids have actually been taught. So researchers are trying to see if children’s general academic vocabulary has grown enough that it enables them to understand passages on topics they may know little or nothing about.

How do you increase kids’ general academic vocabulary? Really, the only way to do that is to build their knowledge by teaching them about specific topics. In order to really understand a new word, kids need to encounter it in a meaningful context, not just on a list of words and definitions. And for kids to remember that new word and be able to use it to help them understand what they read in the future, they need to encounter it repeatedly.

So reading aloud to kids from a series of books on the same general topic, and having them talk about the content is the most effective way to build not just new knowledge, but the vocabulary that goes along with it.

Children can also pick up lots of words that no one has directly taught them. In fact, studies show that’s how they learn most of the vocabulary they need for comprehension. But again, that’s most likely to happen if teachers are building their knowledge systematically. If kids are exposed to a series of texts about wild cats, for example, and they repeatedly see the word links near words like lion and tiger, they’ll probably be able to figure out what a lynx is, even if no one teaches them that word.

The problem, as we’ll discuss in a later episode, is that it can take a long time for kids to build up the amount of general vocabulary that can produce higher scores on a standardized reading test, maybe four years or more. And most studies don’t last nearly that long. Hugh’s study lasted only a year, and that’s longer than most.

Some kids of course pick up more of the knowledge and vocabulary needed for reading comprehension outside school, usually because they have greater exposure to language, which is often a byproduct of growing up in more highly educated families that can make it look like their reading comprehension skills are better.

But an ingenious experiment showed that their advantage has more to do with knowledge than with skills. The experiment was led by a researcher named Susan Neumann at New York University. She and her colleagues took a diverse group of preschool aged kids and read them a book about birds. Some of the kids were from more affluent families, and already knew something about birds, the other kids didn’t. When the researchers tested the kids’ comprehension of the book about birds, they found that the children from affluent families did better. Then the researchers read the kids a similar book about Wugs. If you’ve never heard of a wug, that’s because they don’t exist. By using made up animals, the researchers equalized the children’s background knowledge. This time when they tested kids comprehension. There was no difference between the kids from wealthier and poor families.

But let’s go back to Hugh Catts puzzling over the fact that his year long intervention hadn’t had any effect on kids standardized test scores. Actually, he wasn’t puzzled.

Hugh Catts

You know, by the time these results were coming out, I really wasn’t all that surprised, right? Because I had spent quite a bit of time thinking about comprehension, reading a bit more about or actually reviewing what I had learned earlier about comprehension, and recognized that we were really missing some key components to comprehension and one of them was knowledge.

Natalie Wexler

Hugh knew that the kids in his study had acquired knowledge. The tests showed they had learned the content in the curriculum, and he knew that having knowledge was hugely important to reading comprehension. Even though these children’s standardized reading test scores hadn’t improved. There had been lots of studies on that. Those studies have shown that having knowledge helps readers predict what’s coming up next, it helps them remember the new information in a text, because knowledge is more likely to stick to other related knowledge.

In the words of reading researcher, Marilyn Adams, knowledge is like mental Velcro. Readers are also more motivated to read about a topic they already know something about. And if readers have relevant prior knowledge, it helps them fill in the information authors don’t include in the text, think of all those terms in the cricket and baseball paragraphs that weren’t explained.

Hugh Catts

So authors make certain assumptions about what the readers are going to know. And use that to determine what they’re going to provide within the text. And if you don’t have that background knowledge, you’re not able to fill in those gaps or left for the very incomplete understanding of, of what you read.

Natalie Wexler

He was aware of all this, but many of his fellow reading researchers had come to think about comprehension in a different way.

Hugh Catts

They still had the idea that reading comprehension was something you could measure, and we could intervene and we could improve those, those measures of comprehension.

Natalie Wexler

It hadn’t always been like that.

Hugh Catts

Early on, when I was in graduate school, and right after graduate school there was a great deal of interest in the role that knowledge played in, in comprehension. So, quite a bit of the psycholinguistic work that was done studying how readers understand texts, paid attention to knowledge. Alright, so there were studies early on showing the role of knowledge and comprehension. But over time, we kind of began to pay less attention to it. Forget that that body of knowledge was there.

Natalie Wexler

Researchers began to see comprehension as being similar to other aspects of reading, like phonemic awareness or phonics, something you could teach, have kids practice and then measure directly. There were other factors that shaped researchers’ thinking too:

Hugh Catts

It probably had to do with the fact that, again, we had the idea that the meaning was in the texts, and what the reader needed to do was extract that meeting. So what is it we could teach readers to do that would allow them to take any texts and come to an understanding of it, were their skills that we could implement, teach, that kids students could use when they encounter different subject matters, right. So we pay less attention to the subject matter they were reading, and more to those set of skills that might help us help the students transfer from one particular subject matter to another subject matter.

Natalie Wexler

Hugh says the evidence shows those skills actually don’t transfer from one subject to another. But that’s not the message that has come through to teachers.

If you’re an educator and you’ve gone to a conference or presentation on the science of reading lately, you’ve probably seen at least one infographic that’s designed to show what goes into reading. There were three that have become popular lately. But all of them were created over 20 years ago.

They were designed to show that reading isn’t about just one thing. It’s not just about deciphering or decoding words. And it’s not just about comprehension. It’s about both. That’s certainly true. But he points out that those infographics could be interpreted to mean that decoding and comprehension are pretty much the same, when in fact, comprehension is a lot more complex.

One of these infographics is based on a report that was released in 2000 by the National Reading Panel, a commission of experts. It shows five components of reading as pillars on a Greek temple: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. The graphic has come to be called the Five Pillars of early literacy.

Hugh Catts

And we had infographics that displayed the five pillars of a reading. And in doing so, we began again to think about reading comprehension as if it was like one of those other aspects of reading and the way that you present things influences the way we think about it.

Natalie Wexler

The infographics, he says, have become the standard for the way we think about reading, he sees something referring to the Big Five, those five pillars nearly every day.

Hugh Catts

It’s not that it’s a bad thing, it’s just it’s a simple way of looking at a very complex problem. And that allows us to think about five different areas. But what we really need to think about is the Big One – reading comprehension – and the Little Four: the skills that are part of that.

Natalie Wexler

Then there’s the infographic that depicts something called The Simple View of Reading, it usually shows a box labeled “Decoding”, then a multiplication sign, then another box labeled “Language Comprehension”. All of that is followed by an equal sign, and another box that says “Reading Comprehension”. So Decoding, times Language Comprehension, equals Reading Comprehension.

Hugh says the researchers who developed the simple view wanted to focus attention on decoding at a time when there wasn’t much emphasis on it, and it achieved that purpose.

Hugh Catts

But what it didn’t do was it didn’t fully break down what was involved in the language comprehension component of it.

Natalie Wexler

The boxes for decoding and language comprehension, he points out, are the same size. As with the five pillars, that can give people the misleading impression that these two components of reading should be taught the same way.

The third infographic is more fleshed out. It’s called the Reading Rope or Scarborough’s Rope after the researcher who created it. Her name is Hollis Scarborough. It has two strands that come together, one for language comprehension, and one for word recognition. Within each strand, there are individual threads, including, for language comprehension, background knowledge. Hugh says the Reading Rope does a better job of conveying the complexity of comprehension.

Hugh Catts

But even that needs to be expanded if we’re going to, to understand what we might need to do in terms of instruction to improve comprehension. And again, it’s the presentation. The thread, the threads from the language comprehension are the same size as the threads from the word reading. So we can think about working on word reading for a while, and then we’re gonna go work on some of these threads down here, when in fact, the comprehension part of it is a lot bigger challenge in education.

Natalie Wexler

So while all of these infographics have value, it’s easy to misinterpret them when it comes to figuring out how to help kids comprehend what they read, especially given how deeply entrenched the skills-focused approach to comprehension has become. The infographics appear to put comprehension in the same category as other components of reading, like phonics, when comprehension is actually far more complex.

Another reason the skills and strategies approach to comprehension has become so widespread is that there is evidence showing it can boost comprehension, even as measured by standardized tests. But that evidence doesn’t actually support most of what goes on in classrooms. For one thing, most studies of comprehension strategy instruction have lasted no more than six weeks, and a couple of researchers looked at the data and found there was really no benefit after about two weeks. But American schools teach comprehension skills year after year. There’s no evidence for that.

Also, many of the skills teachers focus on actually have little or no evidence behind them. Things like comparing and contrasting or determining the author’s purpose. The National Reading Panel only found evidence for a few strategies that encourage students to consciously think about what they’re reading, asking themselves questions about the text as they go along, for example.

And none of the skills or strategies will work unless readers have enough relevant background knowledge to understand the text, at least at a superficial level. I could ask myself questions about that cricket paragraph until the cows come home, but I wouldn’t be able to answer them. Plus, as he points out, schools have been focusing on comprehension skills and strategies for decades. And we haven’t seen any improvement in test scores. About two thirds of students test below proficient on national reading tests, and there are wide gaps between students at the upper and lower ends of the socioeconomic spectrum. That’s been true for at least 25 years.

But that doesn’t mean we should abandon the idea of comprehension skills and strategies. Hugh says they do have value.

Hugh Catts

So some of what we called strategies have given students a way to think about what they read. So things like, you know, find the main idea, or comprehension monitoring allows the student to have something to think about while they’re reading that particular passage. And that should have some bit of a bump in how well they understand it, because the more you think about what you’re reading, the more likely you are to understand it.

Natalie Wexler

So strategies can help kids who can read a text and have enough background knowledge to understand it, but maybe aren’t paying enough attention to get its meaning or retain the information. But, Hugh says, skill and strategy instruction doesn’t work, when the primary focus is on teaching a succession of isolated skills, which is the typical approach,

Hugh Catts

Where strategies are probably best used is in a content-rich curriculum, to where a topic is being taught for an extended period of time, and the teacher, both through reading out loud, class discussions, having children reading sentences themselves, talks about the particular domain, and how do you think about that particular domain? Now, of course, that has to be translated to the first or second grader, right. But we can talk about, you know, what’s the most important thing that’s being conveyed in this passage? Right? What specifically is this passage about? Well, what do you think about that? Right? Do you know anything about that? So so that it’s focusing on on a topic that continues from one day to the next day, rather than one day reading about volcanoes practicing a strategy, and the next day reading about the Civil War, you know, using a different strategy, and we’re starting to see these content rich curricula being implemented around the country.

Natalie Wexler

We are, and we’ll be hearing more about that, in the next episode. You will need three teachers who have made the switch to a knowledge-building curriculum, and you’ll hear about what they’ve seen. I hope you’ll join us.

For more information about this episode, visit the Knowledge Matters website linked in the show notes. This podcast is produced by the Knowledge Matters Campaign. You can learn more about their work at knowledgematterscampaign.org and follow them on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Search the #knowledgematters hashtag and join this important conversation. If you’d like to get in touch with me personally, you can contact me through my website, nataliewexler.com.