Innovation Road Trip: Reading Is at the Core of North Carolina School Curriculum, and Students Love ‘Being in Book Arguments’

This is the fourth piece in a new travel blog series on The 74, in which the Knowledge Matters Campaign, part of StandardsWork, will take us on an adventure through classrooms across the country. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter to learn about new installments, and see the full developing series here.

Monticello-Brown Summit Elementary School is one of 71 elementary schools in Guilford County Public Schools, the third-largest school district in North Carolina. It recently adopted American Reading Company’s ARC Core, an English Language Arts curriculum designed to help build children’s knowledge of the world. This is its story.

One might think that a brand-new curriculum (with a lot going on inside of it), in its first year of adoption, and with a newly minted principal, is a formula for disaster. But what’s happening at Monticello-Brown is anything but.

The ARC curriculum is garnering attention from school districts around the country because it looks and feels a lot like the “balanced literacy” with which so many are familiar. This was certainly a factor in Guilford County’s decision to adopt the program.

But ARC Core is, in fact, quite different. While kids work with “leveled books” based on skills they have and have not yet mastered (identified through ARC’s Independent Reading Level Assessment, or IRLA), there’s a sense of very intentional movement through levels rather than languishing in one as all too often happens in traditional leveled programs. There is much celebration when students move to a new level, and surprisingly little competition about at which level students are.

Each level has a set of “power goals” — and every student we talked to could tell us what his/her “power goal” was (such as identifying the antagonist and protagonist in narrative text). Students “conference” one-on-one, or in nimble, flexible groups, with their teacher and are assessed for comprehension, vocabulary, and foundational skills before they move on. If they don’t progress, they know precisely why.

Another difference here is that all of the books are published trade literature, as opposed to leveled readers, which are written specifically to be used in leveled programs. Since the publisher is one of America’s largest distributors of children’s books, districts can customize the units, selecting topics they know will appeal to their students or that match state social studies and science standards. Not only is the core text customizable, but so are all the leveled “bins” that correspond to it, giving students a wide variety of texts from which to choose when working on their power goals.

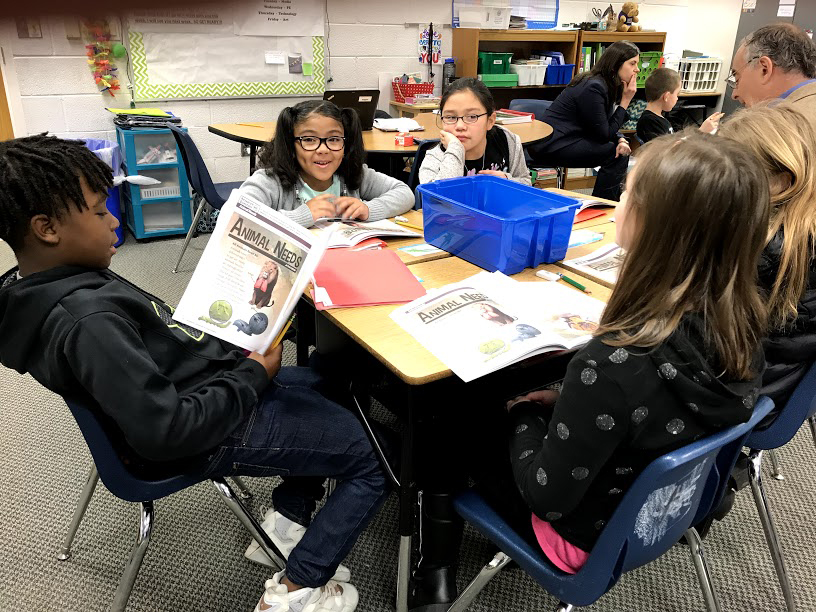

But there’s more. ARC is organized around topic-based units, each of which includes a “research lab” that features a grade-level core text — rich in vocabulary and content — that all students read and around which whole class discussion takes place. Students choose a research topic related to the content of the core text and read additional books at varying levels of complexity to complete a cumulative research assignment. From everything we heard from students, the end-of-unit project is a real highlight of ARC Core.

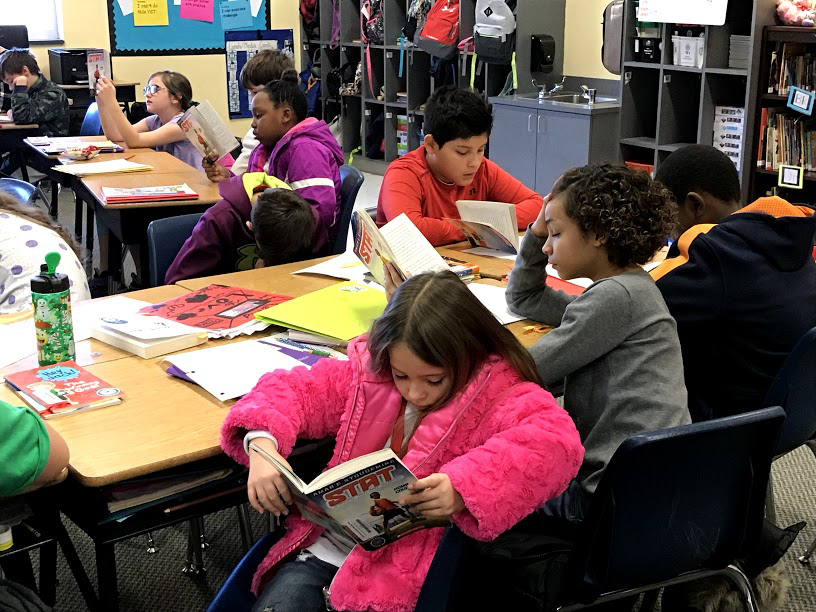

Finally, in addition to IRLA and the Research Labs, ARC includes 30 minutes of independent reading time during which students can choose texts at any level.

The result of all this is that kids are reading — a lot! In fact, it is the volume of reading — and engagement with books — that really is the story of Monticello-Brown Summit Elementary.

What do the kids think about it all?

Fourth- and fifth-grade students: Brock, Bailey, Julio, Camrun, Jaylen, Hunter, Savannah, Riccardo, and Osbaldo:

- ARC gives us the opportunity to read more books.

- At my old school, I didn’t have enough time to read my books.

- Last year I got books that were too hard and I couldn’t read them.

- ARC focuses on one thing, one topic at a time — where you can really get an idea of what it means, what happens, instead of half of this and half of that.

- I like it when we read [a book] together because you can get others’ opinions. I like being in book arguments.

- I never get bored. English and social studies are my favorite subjects.

- ARC is more informational. Last year we just searched for things and wrote it down.

ARC Core has a lot of moving parts. What do the teachers say about it implementing it? From Ashley Martin, Latina Dixon, Alex Faulkner, Melissa Wilson, and Shannon Vaka (curriculum facilitator):

- The rigor in this curriculum is huge. In the beginning, it’s hard. I kept asking myself, “How am I ever going to get them to think this deeply about the text?” (Ms. Martin, fourth grade)

- I would put it somewhere between 1–3 [on a 5-point difficulty scale, with 5 being the hardest].

- I used a program before where all students read grade-level texts, but what’s different here is that they’re [the students] able to make it come alive with books on the same topic. (Ms. Dixon)

- What’s different here is that when we finish with our independent text, they talk with their classmates, and it’s broadening their horizons, they’re sharing with each other, they’re discussing it, and adding to their reading lists. (Ms. Wilson, fifth grade)

- I really appreciate that it took the best of other programs and brought it all together.

- I thought I was going to miss small groups — but this way you get to know the individual readers so much better… you’re working on a very tiny, short-term, specific goal. When they’re ready, you move them.

- The greatest difference I see is with our struggling readers.

Perhaps part of the reason Monticello-Brown’s teachers aren’t more overwhelmed by implementing the new ARC curriculum is because Principal Christopher Scott, a first-year principal in the 2016–17 academic year, when ARC Core was being rolled out, and now chief cheerleader in the district — has invested significantly in professional development. He saw the curriculum being used in summer school, signed Monticello-Brown up as an early adopter, and hasn’t looked back. Scott has also put at least 25 percent of his Title I dollars into supporting professional development, making it possible for the school to benefit from the on-site assistance of an ARC coach for 14 days this school year.

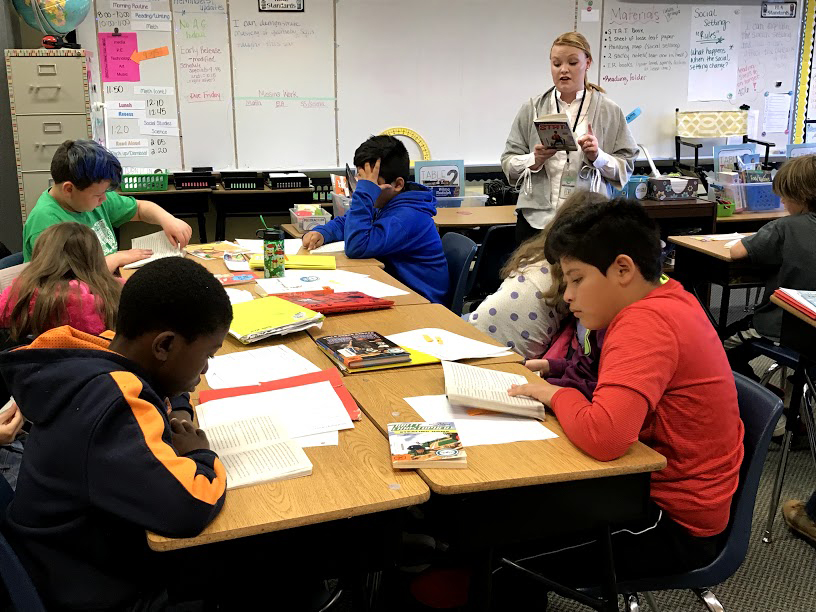

Third-grade teacher Alex Faulkner was just three weeks into using the curriculum (following maternity leave) when we visited and sat in on her coaching session. Faulkner confessed that she was still struggling to figure out in what order to do things — should she work with the skills first or dive into the content? The ARC coach suggested she could, in fact, intentionally connect them.

The book Faulkner’s students were reading was an informational text about bugs. The coach used as an example of a question she might have asked, “Which detail would be most helpful to a bug researcher?” “Oh, I get it; I could blend them together.”

This “aha moment” strikes us as what it’s all about. Privileging content, while not abandoning language arts skills development, is a sea change for many teachers. We saw it on full display at Monticello-Brown. The important point is this: While the curriculum is maturing, teachers are learning, and full implementation across the school and district is taking shape, children are reading and writing more than they ever have, and about more interesting and important topics than previously in their school careers. It will make a mountain of difference in these children’s lives.

David Liben is a senior content specialist on the Literacy and English Language Arts team at Student Achievement Partners. He founded two innovative model schools in New York City where he served as principal and lead curriculum designer.

Barbara Davidson is president of StandardsWork and runs the Knowledge Matters Campaign. A former classroom teacher of students with learning disabilities, she has worked for the past 30 years at the intersection of education policy and practice and has led a number of curriculum development efforts.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)