With nearly 1,100 students filling its classrooms, Laurel Elementary (Laurel, DE) is by far the largest school we’ve visited on the Knowledge Matters School Tour. And its exceptionality doesn’t stop there. The building itself, a sprawling campus of over 150,000 square feet that houses 65 faculty and 35 staff, is also brand new. And so is the knowledge-rich curriculum we were there to see. Bookworms K-5 Reading and Writing, developed by researchers at the University of Delaware and the University of Virginia, is one of the newest entrants onto the high-quality English language arts (ELA) curriculum stage.

Just to keep things interesting, Assistant Superintendent Ashley Giska and Principal Brandon Snyder (a second-year principal, by the way!) decided they would open the school with this new program. Giska had been impressed by the results neighboring Seaford Public Schools experienced with Bookworms the year before, including the enthusiasm and confidence teachers displayed about their learning journey. Since the authors of the curriculum were just “down the road,” Giska knew he would get access to the professional development and coaching support teachers would need. That was a big draw. So was the price. Available free online through Open Up Resources (OUR), even with the purchase of trade books and consumable student workbooks, Laurel would spend a third of what they had previously spent on English language arts curriculum for Bookworms.

Located in rural Delaware, Laurel Elementary serves a diverse student population. Fifteen percent of students are English language learners, the sons and daughters of farm workers, and over 50% live in poverty.

In each one of the stops along the Knowledge Matters School Tour, a “theme” has emerged from our observations of the students’ experience with different content-rich curricula. A year and a half ago at Bryant Elementary, which uses the Core Knowledge Language Arts (CKLA) program, we were struck by how effortlessly students connected content and vocabulary to what they’d learned before. At Monticello Brown Summit in Greensboro (ARC Core) we couldn’t help noting the volume of reading taking place. At Saville Elementary (Wit & Wisdom), it was the engagement of all kids in intellectually rigorous discussion of texts that really blew us away. At Detroit Prep and Detroit Achievement Academy (EL Language Arts) it was how rich content and social-emotional learning came together.

What most stood out at Laurel Elementary was the enthusiasm students and teachers alike had for books and the stories they told; we literally couldn’t get them to stop talking about what they’re reading! “If we’re reading chapter books, they want to read the next chapter. If we’re reading about authors, they want to read more from that author. When we’re reading about a topic, they want more on that topic,” one teacher told us.

“Kids are trying harder because they’re interested in what’s happening,” second grade teacher Erin Brennan told us. “Before they were just reading silly little stories. I see the kids want to try more because they’re interested.”

“I like Bookworms because we learn stuff,” third grader Jose told us. In contrasting Bookworms to what she read last year, second grader Eva told us, “I don’t like books that just have a lot of pictures and only one sentence.” (During our focus group with Eva and fellow first and second graders, they named their favorite books – most of them part of a series entitled, “Childhood of Famous Americans” which the town librarian has apparently had to order more of to keep up with demand from the community!)

Bookworms doesn’t utilize “units” like other core programs do. But that doesn’t mean texts aren’t sequenced intelligently. On the contrary, we were inspired to see texts deliberately stitched together to capitalize on opportunities to build background knowledge and vocabulary. For example, in third grade, students move from Rosa (about Rosa Parks), to When Marian Sang (about African American singer Marian Anderson), to Harvesting Hope (about Cesar Chavez), to Shiloh (about a boy finding a dog he thinks is being mistreated), and later Pinduli (the story of a young hyena who lives in Africa and is different from the other hyenas.) As they work with these texts, students are asked to begin to think and write about injustice – and whether one injustice justifies another.

Bookworms consists of three 45-minute blocks of time – for a total of 135 minutes – every day. The blocks can be scheduled in whatever order the school decides, but the total time, and even the weight given to each block, is sacred.

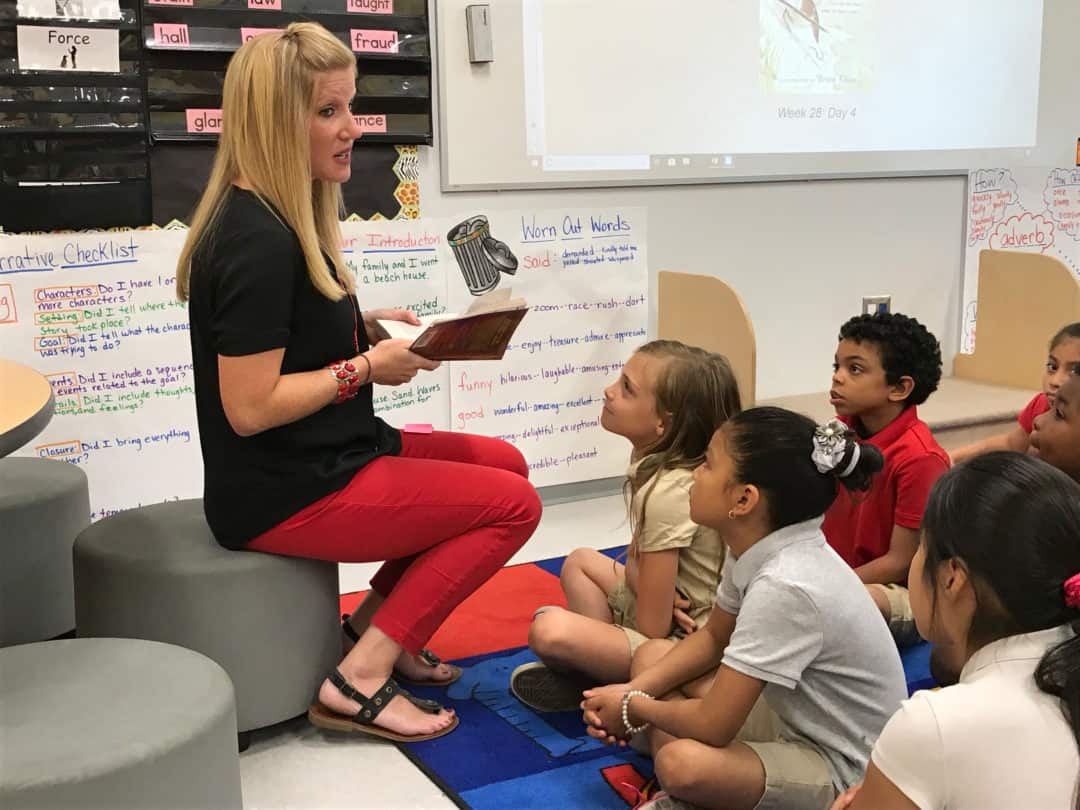

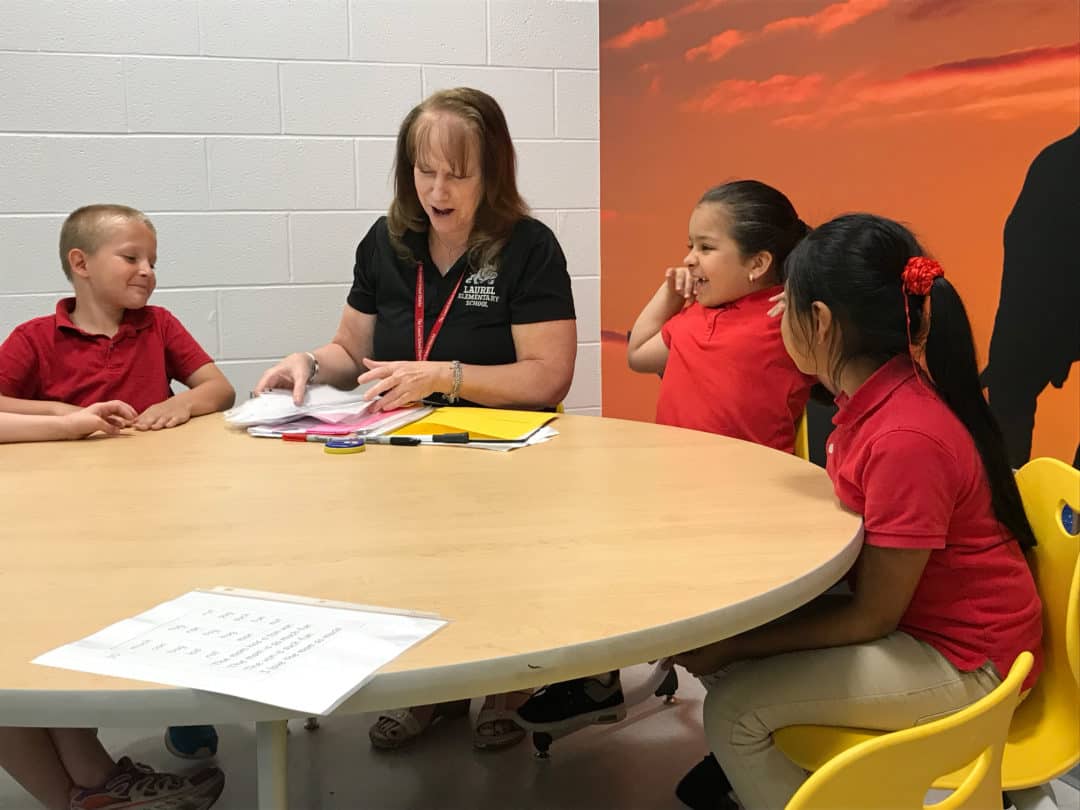

As the name suggests, “Shared Reading” is when everyone in the class is working together to read grade level texts – sometimes literary, sometimes informational. Vocabulary is introduced; books are discussed; and, most interestingly, choral and partner reading occurs (we’ll come back to this in a moment.) The “English Language Arts” block is when students do something, generally writing, with an above-grade level text read by the teacher. “Differentiated Instruction” (DI) is where foundational skills are built, in small, flexible groupings according to assessed student need. While some students receive intensive instruction from the teacher during DI, others are either doing text-based writing or self-selected reading.

To the K-5 classroom teacher, none of this (except maybe the choral/partner reading) will sound especially new. But what IS new is how enthusiastic teachers are about a system that looks pretty – dare we say it?! – “scripted.”

Assistant Superintendent Giska acknowledges that “Bookworms has that specter of ‘scripted’ attached to it” – and we tried to elicit faculty reaction (which we assumed, based on experience, would be negative) either to that characterization or the reality of their day-by-day experience. They were having none of it. One simply gets the feeling these teachers are “over it” about such a rap. Students are engaged and flourishing, planning time is dramatically reduced, and they have enough confidence in the curriculum to know how to appropriately personalize. What’s not to like?

Contrasting her experience with Journeys (the basal reading program used before Bookworms,) fourth grade teacher Jean McCool said, “There was too much you could pick from to do…and you didn’t really know what the things were that you were supposed to be spending time on.” “I spend about 30 minutes a day outside of school planning,” Erin Brennan told us. “Journeys was double if not triple that time, and most of that was spent looking for stuff.” (Note that the school has a 45-minute, grade-level PLC time every morning. And how is that time used? Answer: “For talking about books.”)

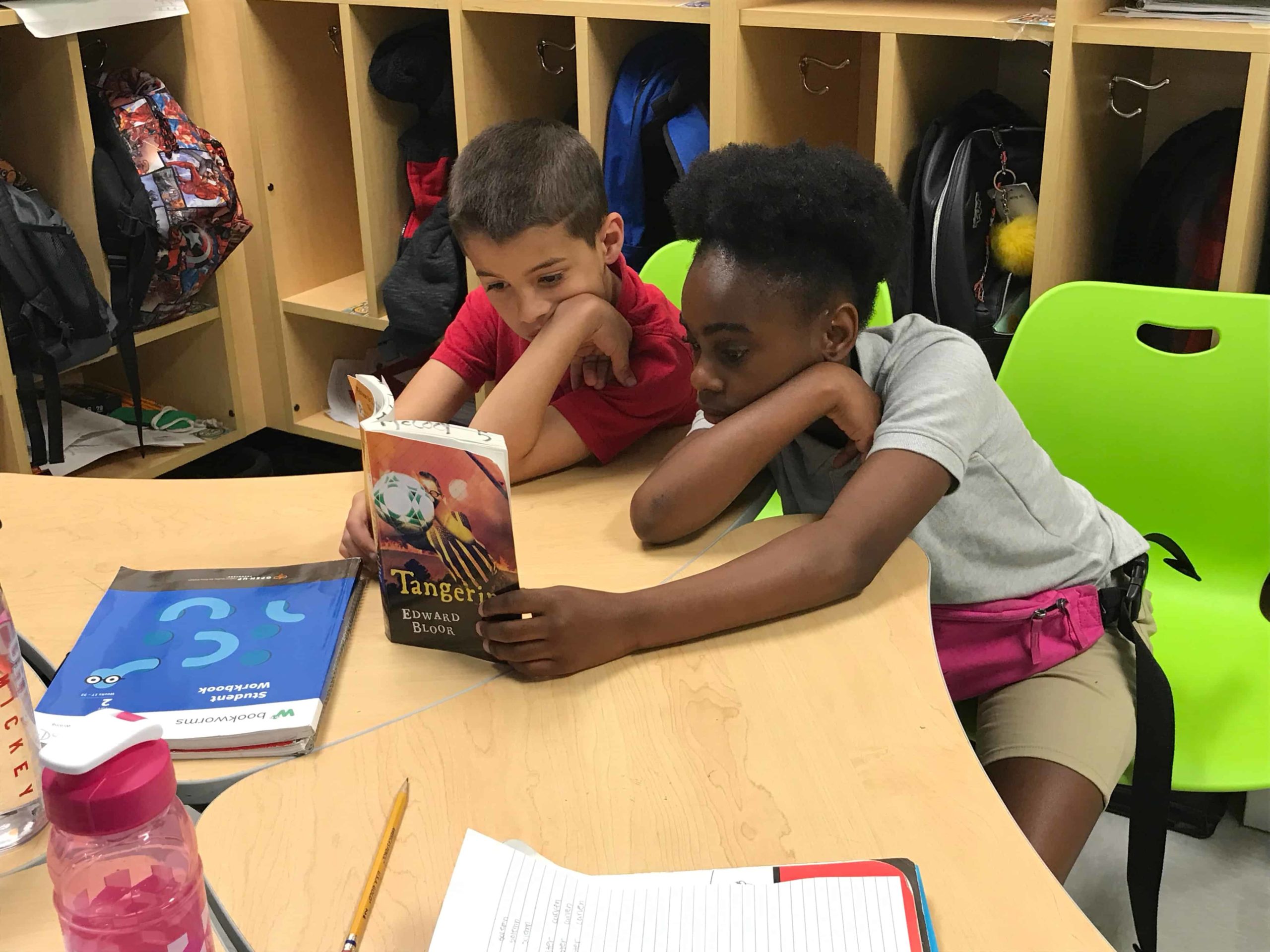

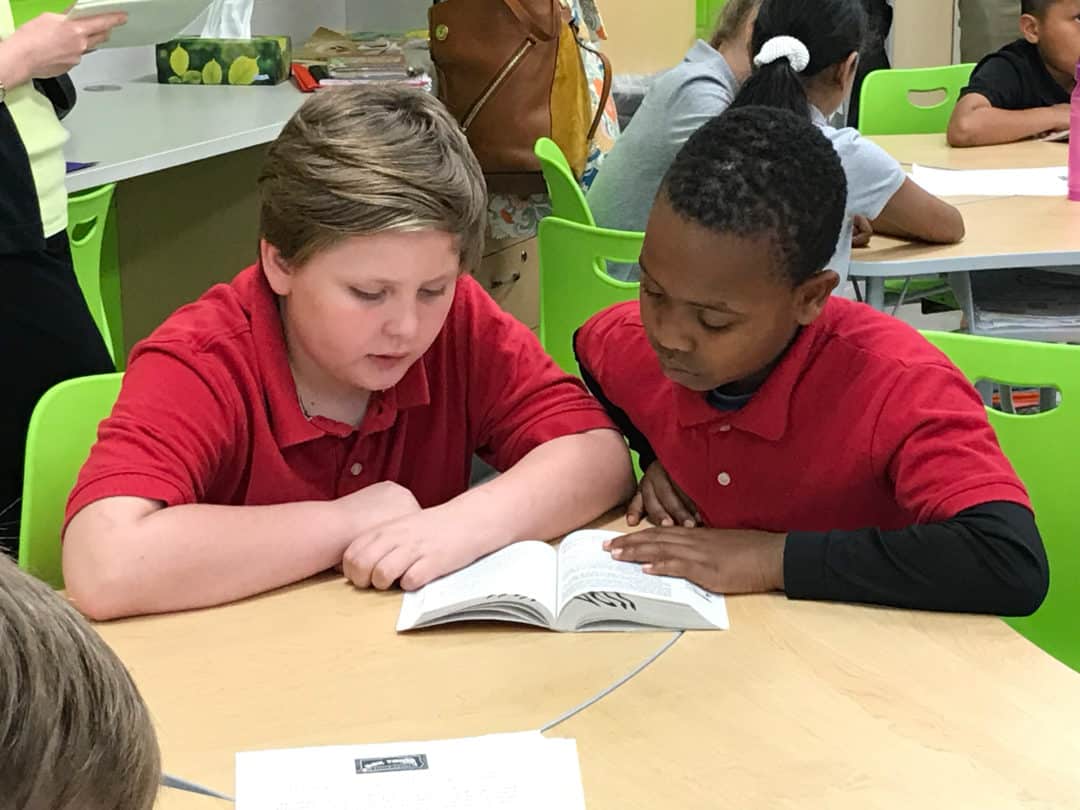

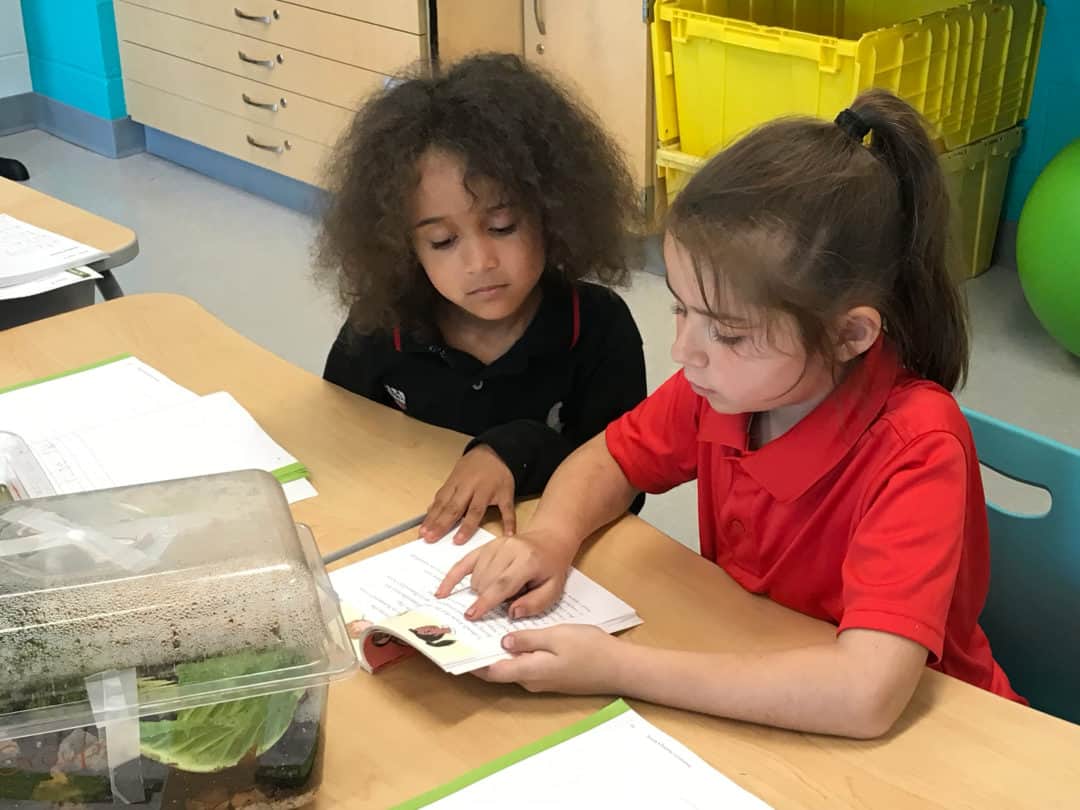

Teachers say the kids respond well to the structure built into Bookworms, including the many fluency routines. Paired reading, an oral rereading of the text for a particular purpose (Bookworms’ answer to “close reading”,) is a staple of the Shared Reading block and one we found particularly intriguing. It matches students of compatible, but not identical, reading ability using a protocol developed by the program’s authors. During paired reading, students work with a partner, sharing the same (actual) book. While not every student we spoke to was enthusiastic about the paired reading, it was clear the students who most benefited from “sharing the decoding load” (as the authors put it) liked it a lot.

The other thing students respond well to are the texts themselves – so much so that Principal Snyder has had to get strict about kids taking their noses out of their books when walking out to the bus! Bookworms developer Sharon Walpole was intentional about selecting books that have this kind of addictive quality, to include leaning on book series. “We want students to become bookworms” she says in one of her training videos.

Throughout the Knowledge Matters School Tour, we have attempted to showcase different models for how content knowledge could be advanced during the English language arts block. It has been fascinating – and deeply gratifying – to discover that there are increasingly varied, high-quality options for schools about how to do this. Bookworms K-5 Reading and Writing definitely belongs in the club!

The Authors

Barbara Davidson is President of StandardsWork and runs the Knowledge Matters Campaign. A former classroom teacher of students with learning disabilities, she has worked for the past 30 years at the intersection of education policy and practice and has led a number of curriculum development efforts. Special thanks to education writer Natalie Wexler and Silas Kulkarni from The Teaching Lab for joining us on our visit and contributing to this article.